Junior Stacy Saucedo has three closets.

The first is filled with old clothes that don’t fit, the second with hand-me-downs from Stacy’s older sister, and the third with everyday wear and special items.

Though the sheer number of clothes may seem overwhelming, a closer look reveals the hidden thread of a deeper story. Many fabrics show the wear and tear of years of use – the oldest has passed from Stacy’s aunt to her mother, to her older sister, and then to her. When the time comes, it will be passed on to Stacy’s niece, who is already wearing Stacy’s kindergarten clothes.

This tradition, though embedded in Hispanic culture, is entirely contrary to the modern world of fashion and the burgeoning trend of fast fashion.

Impact

Fashion itself isn’t the villain – clothes are a necessity. Instead, it is fast fashion that is exacerbating fashion’s environmental impact. Earth.Org describes fast fashion, a term coined by The New York Times in 1990, as “cheap and low-quality clothing that are rapidly produced and are cycled in and out the market quickly to meet new trends.”

Statistics back up the growing trend; according to the UN, clothing production doubled between 2000 and 2014, with the average consumer buying 60 percent more than 15 years ago (as of 2018), but keeping each item half as long. In the US, one survey found that 20 percent of clothing is never worn (Columbia).

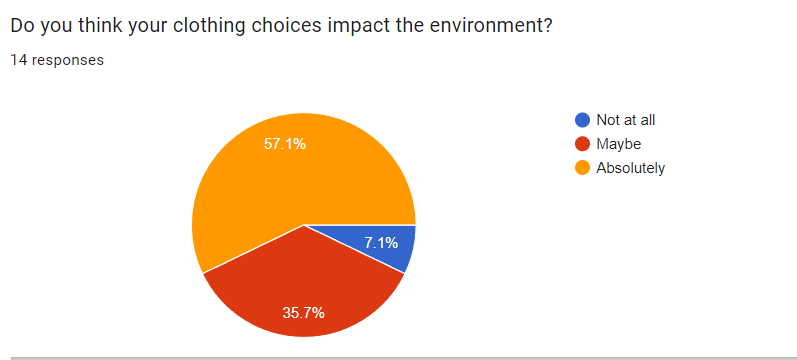

The national and global statistics are mirrored by students. In a survey taken by the RoundUp, student estimates for how many pieces of clothing they had ranged from 30 to 300. As for how many had never been worn, estimates ranged from “70% of the clothes I have” to just 4 to 150. Though these consumption habits line up closely with the standard definition of fast fashion, over a third of respondents still say that they think their clothing choices only “maybe” impact the environment.

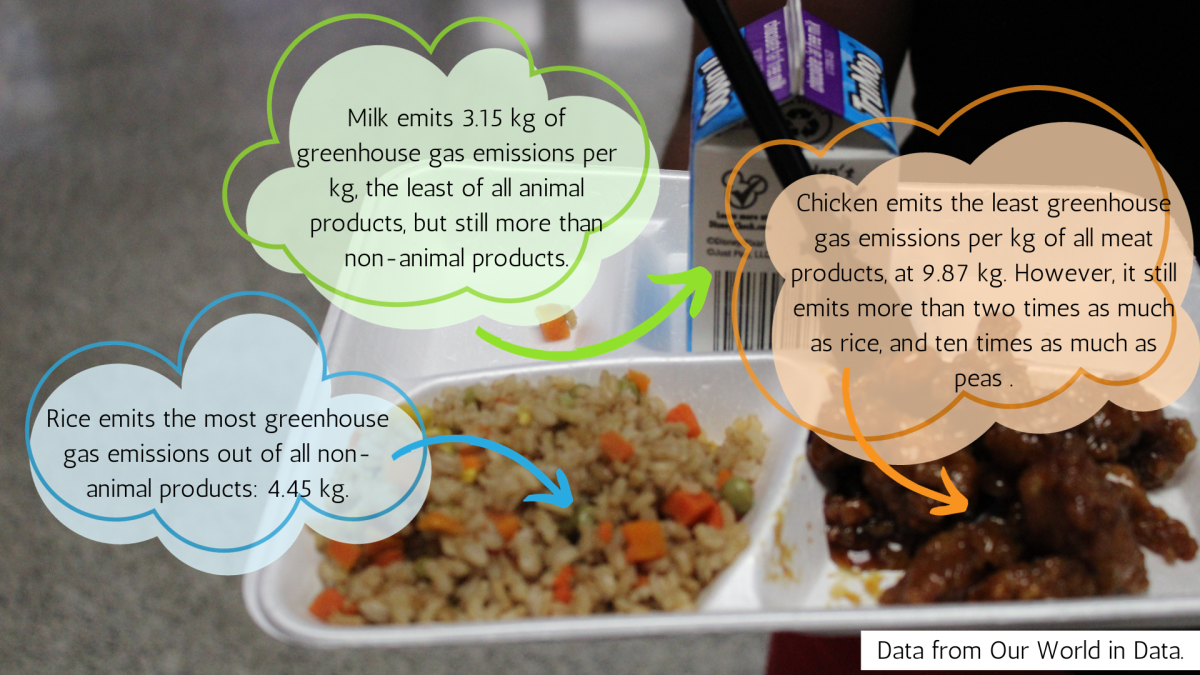

However, fast fashion’s rise has serious, clear-cut implications for the environment. The fashion industry is responsible for 8% of global emissions – textiles production creates 1.2 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions each year, more than international flights and maritime shipping combined. The fashion industry also consumes 93 billion metric tons of clean water each year, half of what Americans drink annually.

Fashion also contributes substantially to pollution. Clothes production processes like dying use 43 million tons of chemicals annually, accounting for 17 to 20 percent of global industrial water pollution. Additionally, garments release plastic microfibers when washed, contributing to half a million tons of ocean pollution each year.

While elimination isn’t the goal, individuals can take steps to remove themselves from the fast fashion trend.

Individual feasibility

Fashion is fortunately an area in which individuals have a lot of power. Overconsumption is the biggest driver behind fast fashion, but it lies almost entirely in the consumer’s hands. For instance, in response to the RoundUp survey, student estimates for how many clothing pieces they buy each year range from 10 to 100. The simplest solution to fast fashion on the part of individuals is to buy less and wear more.

Another driver of fast fashion is the waste aspect; the follow-up to constant consumption is constant disposal. Students estimate that they keep their clothes anywhere from one to three years at best to three to four weeks at worst. One respondent simply put “until I don’t want it/until it has damage”, illuminating the role of quality clothing in fighting fast fashion. Low-quality clothes that quickly rip or tear drive the consumption cycle faster, while higher-quality clothes that last longer can slow the cycle down. Asking what clothes is just as important as asking how many.

How clothes are cared for after they are bought also plays a role in preserving their quality. Domestic washes can release hundreds of thousands of fibers into the environment. Washing at a lower temperature uses less energy, and adopting simple habits, like turning clothes inside out, can increase wearability.

Additionally, clothing materials have varying impacts on the environment. Cotton, for instance, is known for being water-intensive and requires heavy pesticide use. Further, as a synthetic material, polyester uses oil in its production process, contributing far more greenhouse gases per kilogram. On the other hand, hemp is known for being one of the most sustainable clothing materials, requiring little water and pesticides. Most clothing materials can adjust their production processes to be organic, reducing their environmental impact by far.

Lastly, different brands also vary in their impact on the environment. Good on You rates brands on a scale of 1 to 5 for people, planet, and animals based on greenhouse gas emissions, water use, as well as worker safety and animal welfare. For instance, Under Armour is rated “not good enough”, a step up from “we avoid”, earning a 2 out of 5 on all three scales. However, while consumers can choose where to buy their clothes, company practices are ultimately out of individuals’ hands. That is where the shift to systemic change begins.

Systemic challenges

Many brands have collections that use organic and recycled materials, including H&M Conscious, Adidas x Parley and Zara Join Life. However, sustainable brands as a whole tend to cost more for consumers due to the higher prices of sustainable materials and costs associated with sustainable production practices.

Additionally, obtaining organic or environmentally friendly global certifications is a responsibility on the part of the producer. Individual choices are often exponentially difficult in comparison to the steps that companies themselves can take to reduce their fashion footprint. Consumers can choose where to spend their money, but the choice to buy sustainably needs to be made available to them first.

Ultimately, proposed reforms of the fashion industry extend much further than individual brands. The textile industry as a whole can reduce its use of non-renewable energy and decrease carbon dioxide emissions and manufacturers can decrease the use of chemicals. Further, an Extended Producer Responsibility could combat the allure of cheap clothes that deteriorate quickly by requiring producers to take back products at the end of their lifespans and assume responsibility for recycling the material.

Though approaches to reforming the fashion industry vary, the goal is relatively consistent: a circular fashion industry where materials are used as long as possible, and waste is reused for new products.

Call to action

The simplest place to begin in the fight against fast fashion is buying less, taking note of the multiplicity of stories clothing can tell – if it’s rescued from a premature date with the dumpster.