“Chicken nuggets, fries, and green grapes.”

My friend replies to my somewhat out-of-the-blue, definitely nosy question with a touch of wry humor and a healthy dose of confusion.

“Does this secretly have something to do with climate change that I’m not seeing?”

My response? An enthusiastic, all-caps “YES!!!”

What’s on our plate isn’t typically the first thing to come to mind when thinking about climate change. But, diet is something we all share, three times a day, and it adds up.

What are some ways that diet affects the environment, both good and bad? To what extent? From the merits of vegetarianism and veganism to systemic agricultural issues, our diet has a multi-faceted and important role to play in the climate crisis.

Impact

Agriculture isn’t a flashy climate villain, but its impact on the environment is undeniable and wide-reaching.

Agriculture uses almost half of the world’s vegetated land and generates one-quarter of annual greenhouse gas emissions – more than all of transportation! Most of these greenhouse gas emissions stem from methane from cattle, nitrous oxide from fertilizers, and carbon dioxide from deforestation. Additional negative effects of the food production system include the use of antibiotics among farmed animals, which leads to antibiotic resistance in humans, and diseases that originate from livestock and spread to humans.

However, agriculture is a vital sector. It isn’t something to be eliminated, but rather something that calls for transformation by isolating and mitigating its most damaging parts. For instance, ruminant livestock like cattle, sheep, and goats use ⅔ of global agricultural land and account for 50% of agricultural production-related emissions on their own. Reducing consumption of these products can have disproportionate positive repercussions.

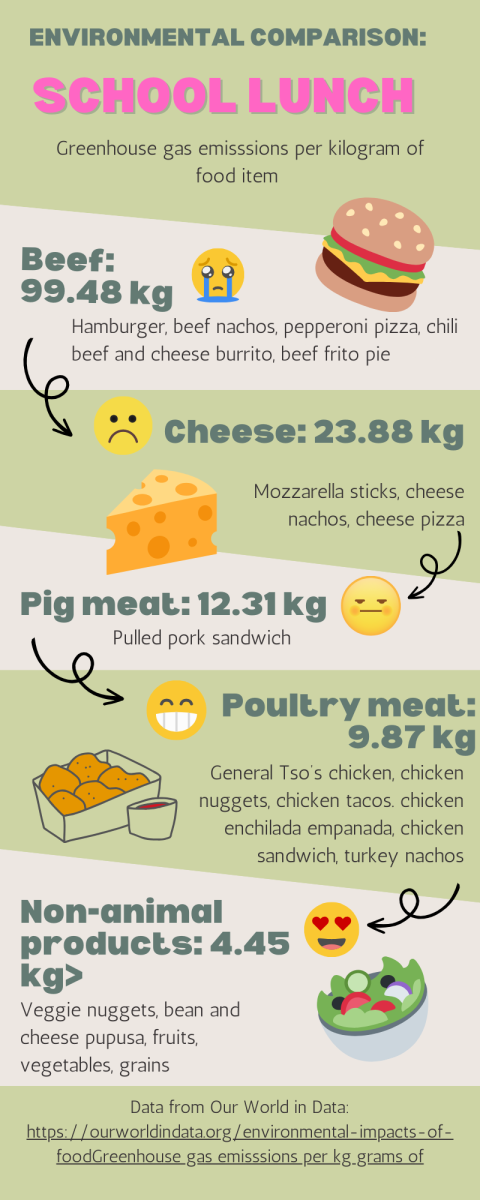

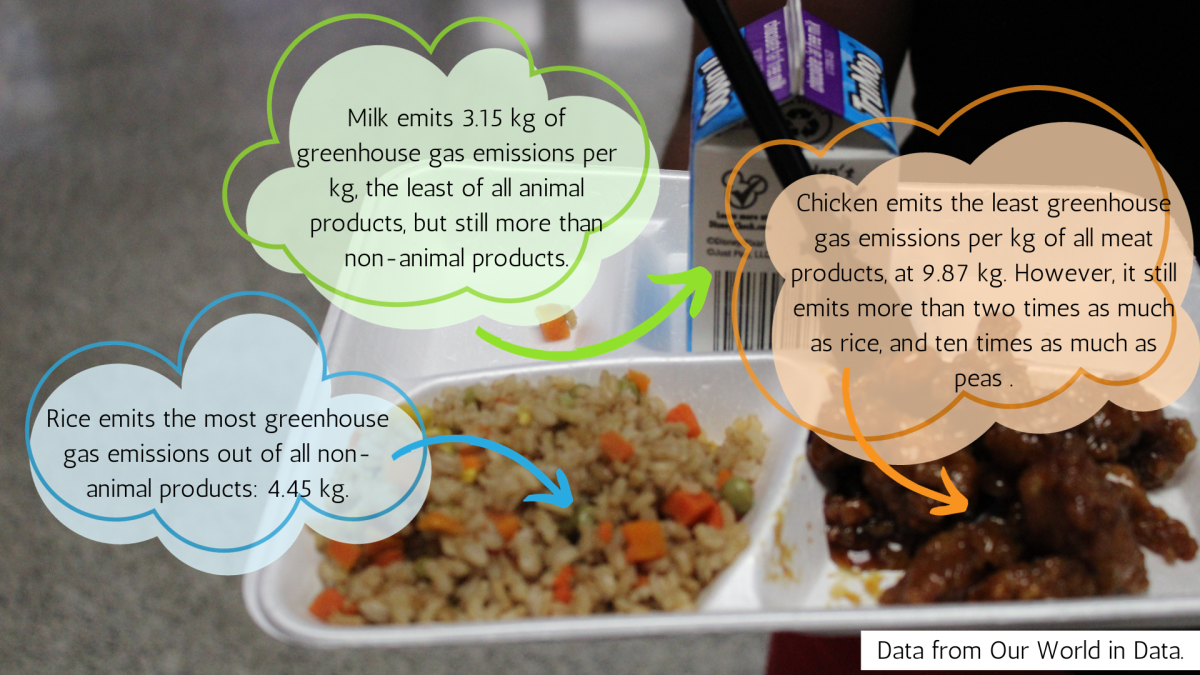

Further, as a whole, meat and dairy tend to have higher carbon footprints than plant-based foods. Producing 100 grams of protein from beef produces 90 times more emissions than getting the same amount of protein from peas. As a result, plant-based diets like vegetarianism and veganism are much better for the environment than meat-heavy diets, particularly diets that include a lot of beef, lamb, or goat.

Other animal products have varying environmental impacts that can make it possible for non-vegetarians to make dietary choices that are also conscious of the environment. From highest to lowest in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, animal products rank beef, lamb and mutton, dairy, prawns, cheese, pig meat, and poultry meat. Plant-based foods such as nuts, potatoes, and bananas as a whole have lower emissions by far. BBC offers a useful tool to calculate the environmental impact of different foods based on type and frequency of consumption that also provides insight into the energy and water usage of the food.

–

Having successfully inundated my friend with statistics on the relationship between diet and climate change, I, like any respectful journalist, sent a follow-up: “Did our discussion affect your choice or cross your mind during lunch today?”

My friend texted back that she had a chicken sandwich and considered that chicken would be environmentally better than beef. And, best of all, she’ll be more aware of what she eats moving forward.

Followed by a thumbs-up emoji.

–

My friend echoes a sentiment all too common in the discourse about climate change: our daily choices seem inconsequential. Yet, some simple calculations reveal the extent to which our daily choices add up. The school cafeteria’s hamburger is made with three ounces, about 84 grams, of beef. According to BBC, just eating one hamburger made with 75 grams of beef weekly can contribute to 604 kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions in a year – the equivalent of driving a petrol car over 1,500 miles. In comparison, a cheese-based option that many of the cafeteria vegetarian options consist of, like nachos or mozzarella sticks, would create 75 kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions if consumed with the same frequency, less than 8 times as much as beef.

If 1,000 students just at Clements are choosing one over the other, that is a 529,000-kilogram difference in annual greenhouse gas emissions that could be saved if people like my friend, like any student, began changing our daily habits.

Now, at the actual global scale of billions of people, diet plays a key role in the climate crisis, to the extent that without shifting dietary practices, the world will not meet the target of keeping warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100. On the other hand, if fifty percent of the world’s meat and milk consumption were to be replaced with plant-based alternatives, the world could halt ecological destruction that results from farming, like deforestation, and reduce agriculture-related greenhouse gas emissions by 31 percent by 2050.

Food holds enormous power at the scale of the global climate crisis but also offers clear pathways to empowered individual actions. It is the perfect place to make change happen.

Individual feasibility

How feasible is making one’s diet more climate-friendly? As kids, students aren’t always in control of what they eat, but they also have some choices, like the one made every day in the lunch line. Choosing between a food that creates 50 kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions and a food that emits less than five on a consistent basis can make a significant impact on an individual’s carbon footprint.

For instance, at the scale of school lunch: hamburger<macaroni and cheese<chicken nuggets<bean burrito. Similarly, pepperoni pizza<mozarrella sticks<chicken pasta<veggie nuggets. Inconsequential as the choice may seem, the environmental impact is not, especially when compounded by many people, repeatedly. Though our need to eat will have an inevitable impact on the environment, to what extent remains in our hands.

Other ways to start eating more sustainably include taking incremental steps like making meat the side dish rather than the centerpiece, adding one meat-free dish each day, or creating a meatless day of the week. Alternatives to meat and dairy include tofu, nuts, peas, and beans, as well as plant-based cheeses, yogurt, and kinds of milk, all of which are increasingly being made available to consumers in grocery stores and even to students in school, and emit far fewer greenhouse gas emissions than the traditional animal products.

Above all, it is important to abandon an all-or-nothing mindset. Transitioning to a more sustainable diet isn’t either going completely vegetarian or nothing at all, but instead looking for and sometimes creating opportunities for change.

Systemic challenges

As is true concerning all climate solutions, individual choices play an important role, but systems must follow through. The World Resource Institute issued a report detailing what the world as a whole must do to address the climate crisis and the issue of world hunger.

The report says that the world as a whole must raise productivity, manage demand, protect natural ecosystems, target reforestation, and moderate ruminant meat consumption. The report also proposes climate mitigation related to agricultural production such as the use of fertilizers and energy use and technological innovation, such as crop additives that reduce methane emissions from rice and cattle or plant-based beef substitutes, which will require more research and development funding and flexible government regulations.

Though individuals don’t have control over where government funding is directed or what regulations exist in the agricultural industry, we have control over our choices, which collectively hold sway in the broader picture. Changes may depend on the aid of government policies, but they do not need to start there.

Call to action

The why and how our diets need to and can change is clear; agriculture is a key contributor to current greenhouse gas emissions and will be a deciding factor in whether the world can meet climate targets in the future. At the individual level, the knowledge of how different foods weigh against each other in terms of environmental impact can influence what dietary choices are made on a consistent basis.

Change, however, is never absolute. One choice, one meal, is a worthwhile starting point.

. • Oct 2, 2023 at 10:14 am

least obvious fed