It’s both a humble and humbling endeavor.

Great, rumbling heroes in the early morning and mid-afternoon, 470 buses wind through neighborhoods, over bridges, and under shadowy canopies, traversing over 5 million miles annually to deliver its riders to the 87 schools in Fort Bend Independent School District.

Yet as much as these yellow giants are a hallmark of the American educational system, they have also come to be a point of contention – the traditional school bus is powered by fossil fuels but is at the same time an indispensable part of daily life for everyone from sleepy-eyed elementary schoolers to sullen, tired teens.

At the infinitesimally thin border between tradition and change, we find ourselves at a cliff – it is now up to us to find a way to rappel down, swinging between the rocky mountainside of a hectic reality and the free fall of a future marked by an enormous environmental challenge.

Impact

Transportation has an outsized presence nationally; it accounts for 28% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, more than any other sector. High greenhouse gas emissions from transportation in the U.S. can be attributed to historical investment in highways rather than public transit – wealthy countries with a history of transit-oriented development like Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Germany, have higher use of public transit and lower emissions from transportation.

Over half of greenhouse gas emissions from transportation are climate-change-causing carbon dioxide emissions resulting from the combustion of petroleum-based products, like gasoline and diesel fuel, in internal combustion engines. The largest sources of transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions include passenger cars, medium- and heavy-duty trucks, and light-duty trucks, including sport utility vehicles, pickup trucks, and minivans.

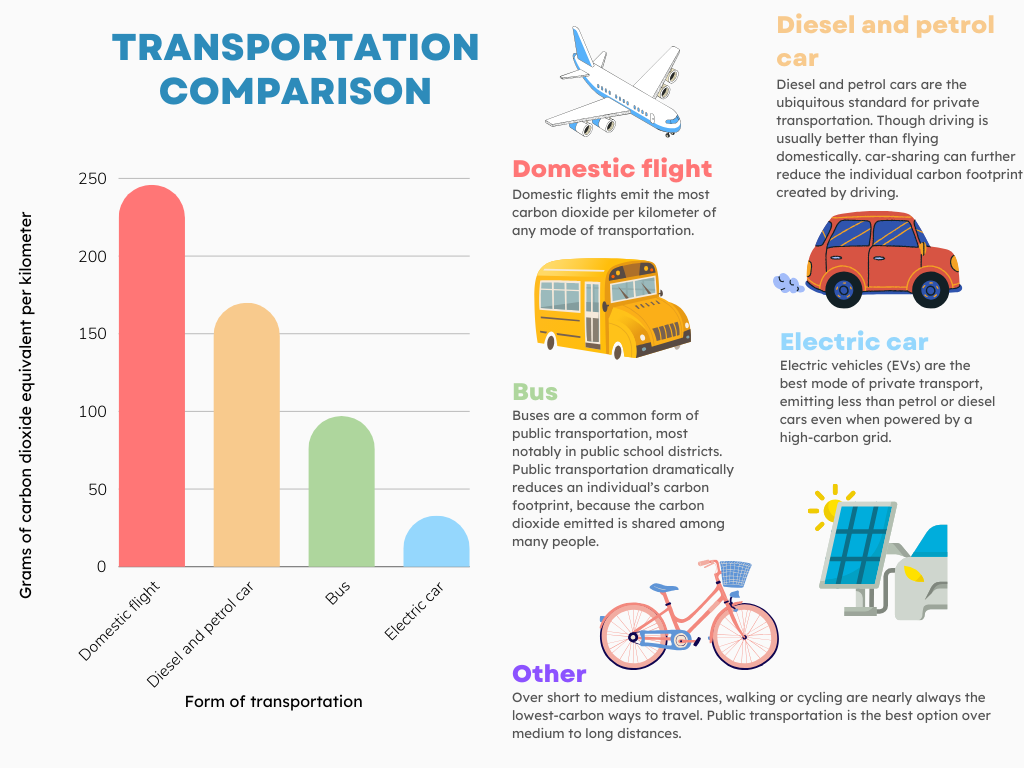

However, the environmental impacts of these modes of transportation differ drastically. From greatest to least emissions per kilometer, they rank as follows: domestic flights (246 g), diesel and petrol cars (170 g), short and long-haul flights (about 150 g), buses (97 g), electric cars (47 g), and bikes (around 30 g). Flights have by far the greatest carbon footprint; an analysis from the Guardian showed that even a short-haul return flight from London to Edinburgh contributes more CO2 than the mean annual emissions of a person in Uganda or Somalia.

However, beyond just steering clear of flying whenever possible, this hierarchy has other practical implications. For instance, using a bike instead of a car for short trips reduces emissions by 75% while taking a train instead of a car for medium-length distances cuts emissions by around 80%.

Overall, walking or cycling are the lowest-carbon ways to travel over short to medium distances, while trains are the best option over moderate to long distances. While traveling domestically, driving is almost always better than flying. However, actions like carpooling can dramatically reduce individual carbon footprints.

Individual feasibility

Even fully aware that walking is a more environmentally friendly way of getting around than driving or taking a bus, there are still millions who rely on fossil fuels to get to school or work, and changing ingrained habits and systems can be tedious, difficult, and even impossible.

For instance, switching to public transportation is not always a feasible call to action; private cars are often a necessity for individuals who live in suburbs or rural areas. Further, an individual’s ability to walk or cycle in the area they live varies greatly by city. San Francisco, New York, and Boston are considered the most walkable cities in the United States, with ratings of 89, 88, and 83 out of 100, respectively; Minneapolis, Portland, and San Francisco are considered the top three bikeable cities.

On the other hand, Sugar Land has a rating of 28/100 for walking and 37/100 for biking. Sidewalks are bumpy, traffic is fierce, and on top of that, what is a teen to do when it rains? Further, for students who live more than a mile or two away from school, walking and cycling are out of consideration entirely, and the mighty school bus comes into play again.

Electric vehicles also have a dominant presence in the discussion of transportation and climate change, but their feasibility is also dependent on factors that may be beyond individual control. Though electric vehicles (EVs) are considered the best mode of private transportation, concerns about cost leave many wary of making the change. Although there are tax incentives for buying EVs that range in the thousands of dollars, the upfront costs, maintenance costs, and depreciation tend to make EVs pricier than their traditional counterparts.

In a situation limited by finances or location, the true spirit of individual climate action cannot be forgotten – climate solutions are intended to empower, not shame. It falls to the system to ensure that the little people – who are tasked with going about their day-to-day lives and facing the looming threat of climate change – are not overlooked.

Systemic challenges and changes

Slowly, there is a truth coming to light in the public eye – as much as we tend to be forward-looking when discussing climate change, the issue is one of the present, whether in the form of unexpected freezes or unprecedented heat. As slow and tedious as the process is, the solution is starting to be, too.

For instance, though individuals still face financial barriers to buying EVs, there already exists a substantial tax incentive in place. There are also efforts to electrify transportation at the national level, in a way that may touch students’ lives: as part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, $500 million is now available to begin replacing school buses with clean, American-made, zero-emission buses – and this money is only the first round of funding out of a $5 billion investment for low and zero-emission school buses over the next five years.

Yes, change is costly and difficult. But we cannot continue to cling to a crumbling cliff – whether or not we are prepared, we will eventually tumble into free fall.