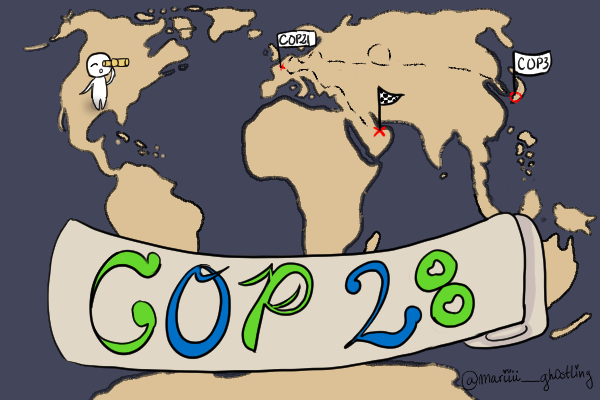

1997.

Two decades before I am born, COP3 convenes in Kyoto.

2015.

As Paris hosts COP21, I’m putting the finishing touches on my elementary school presentation, the title slide emblazoned with “GLOBAL WARMING” in thick flourishes of text.

2023.

COP28 reaches its end in Dubai – this chapter of my story, and the world’s story, is still being written.

From two historic landmarks to the present day, COP has mirrored the progression of the climate movement, from its public image to its call to action. Yet, as new knowledge and perspectives emerge, the climate movement must listen and respond – even to the voice of one student. In three historic COPs are three perspectives to illuminate the path forward.

COP3, Kyoto: Polar Bears

1997. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is published in late June. As the summer concludes, Princess Diana dies in a late-night car accident. When fall fades and the winter months encroach on the year, the Kyoto Protocol, a commitment to lower greenhouse gas emissions, is adopted by a United Nations committee.

Though COP3 is today best remembered for that first treaty, it in reflection serves better as a snapshot of the climate movement’s early days, which were best exemplified by one animal: polar bears.

They were on signs. Made into costumes. Even transformed into giant inflatables.

The polar bear was the defining symbol of the early climate movement, exemplifying the dangers of a warming planet: melting Arctic sea ice and endangered, adorable animals. Yet, in light of the evolving discourse and lived experiences of the past decade, especially the past year, it is time for the face of the climate movement to change.

Most people, including myself, have never encountered a polar bear. They’re cute, but my emotional attachment to them is limited. On the other hand, I see people every day, and the empathy I feel for people and their struggles is far more vast than what I can feel for animals, as much of an environmentalist as I am.

In light of this, the climate movement must reorient itself to highlight a key truth: climate change is, at its heart, about people.

Heat waves and natural disasters have increased in intensity and frequency due to climate change, and in the past year alone, the human cost has been clearer than ever; Typhoon Doksuri in East Asia killed 26 people, and wildfires in Maui left 388 people dead or missing. Even when not deadly, the impacts of climate change can be obtrusive and threatening, from Storm Hilary in California putting millions at risk of flooding to heat waves driving fires across the Mediterranean.

Yet, in the worst of disasters lies another lesson. According to a 2021 EPA report, socially vulnerable populations, such as low-income or minority populations, are most likely to live in areas with the highest levels of projected climate change impacts, including extreme temperatures, increases in air pollution, and flooding caused by sea level rise.

While the climate movement is about animals, it is not just animals. And while it is increasingly being recognized that the climate movement is about people, it is not just people. It is a matter of justice, too, and must be addressed with rightful urgency.

My perspective is indeed limited to my lifetime – I wasn’t even alive in 1997, but justice is a timeless ideal. Perhaps justice has waited this long to make its way into the climate movement because it first had to be embraced in racial, social, and political contexts. Now, having come of age in the era of Black Lives Matter and StopAAPI Hate, it is finally time to transform the face of the climate movement, moving the spotlight from polar bears to people.

COP21, Paris: Greta Thunberg

2015. In the year or so after COP21, which today is best remembered for the Paris Climate Agreement, I entered fourth grade. Through the mysterious powers of the internet, I discovered the existence of global warming, and it rocked my world. Scared and infuriated, I panicked.

For my year-long GT project both that year and the next, I read through dozens of NASA articles to craft and deliver passionately worded presentations about “GLOBAL WARMING”. When I learned that the United States was exiting the Paris Climate Agreement, I paced around the classroom in such apparent anger that my teacher told me to calm down. But I was not alone.

Another year or so later, Greta Thunberg held her first school strike for the climate, a lone figure outside the Swedish parliament building. In the following years, similar strikes spread around the world and Thunberg established a name for herself through searing, critical addresses to world leaders. I idolized her.

Yet today, as an amateur activist who has watched years and years of anger and criticism driving the climate movement, I am ready for the movement to mature.

First, it is important to acknowledge that anger is justified – it’s true that fossil fuel companies knew about global warming but refused to tell the public, and that governments have been slow to address the crisis. What should be contested is not anger’s justifiability, but rather its effectiveness.

Anger is inherently limited because it creates an “us” and a “them” – us, the activists and civilians and victims, and them, the fossil fuel executives and beef eaters and conventional car drivers and electricity users and people who take showers longer than five seconds. Anger perpetuates a narrative of elitism that is entirely contrary to what the climate movement should be about.

The approach the climate movement takes in communicating its message is as important as the message itself; people cannot believe that we are advocating to protect the Earth and the people in it when we are throwing soup at historical paintings and blocking highways. Only through constructive means can we earn support toward a constructive cause.

We – billionaires and working-class families all – are united by the need for a home. As a result, the climate movement should emphasize the true vision of success: a safe home. Rather than shame and alienate, we must emphasize hope to motivate people and garner support.

I am not a stranger to righteous anger – my younger self felt and expressed it fully. But looking back, my message was lost in anger. Being on the receiving end of anger fosters fear and hopelessness rather than motivation – and what the climate movement needs most is a motivated support base.

Only hope for a better future can garner widespread support. Only love and empathy for each other as well as those who will inherit our legacy can motivate action. Through shared human emotion, the climate movement must maintain its focus on the ultimate goal: preserving this planet for all who inhabit it.

COP28, Dubai: Where We Are Now

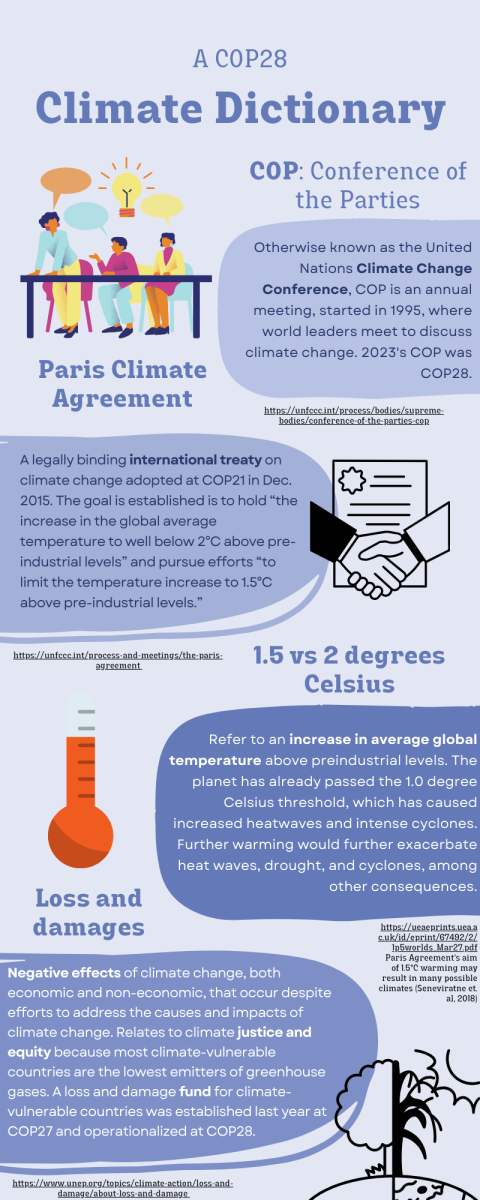

2023. A historic year – confirmed to be the warmest on record. In November, two days were warmer than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels – briefly but surely breaching the goal set by the Paris Climate Agreement eight years ago.

In early December, as the heat at last relinquished its grip on the Northern Hemisphere, COP28 struck a similarly historic chord. Countries operationalized the loss and damage fund, with countries like the United States, Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom pledging millions of dollars to cover the costs of climate change-related natural disasters in developing countries.

At first blush, the idea may seem a bit unfair – shouldn’t everyone give something? But the loss and damages fund is deeply rooted in climate justice and the idea of equity; most developing countries are the lowest emitters of greenhouse gases but are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, while most developed countries are high-emitters, but less vulnerable.

Blindly distributing the responsibility to take action to every country is not equality – it enforces inequality when two countries that start from different places are forced to run the same race. Instead, the climate movement must foster equity at both the global and individual levels.

Responsibility should be distributed only after accounting for situational and historical factors. At the global level, equity takes the form of loss and damage funding, an area in which there have been major gains. However, equity at the individual level remains underappreciated.

In 2019, the richest 1 percent were responsible for 16 percent of global carbon emissions, the same as the poorest 66 percent. It doesn’t make sense to ask the 66 percent to commit as much time, money, and energy to individual climate action as the 1 percent, but the climate movement’s calls to action are still often made indiscriminately.

Ditch fossil fuels!

For a wealthy business owner, this might be feasible, but for a rural farmer, fossil fuels may be the only source of cooking fuel available.

Go electric!

As a high school student who can’t drive and rides the bus to school every day, I can’t – not without reforming public transportation in its entirety. Though there are countless other ways for individuals to reduce their carbon footprint and contribute to the climate movement, people will only feel ready to participate when calls to action are inclusive.

People.

Humanity.

Equity.

These are the pillars that must usher in a new era of the climate movement, an era made of the youth of today. 1997, 2015, and 2023 are not just historical landmarks in COP’s history; they are pivotal stages in the development of a millions-strong movement and a generation coming of age in the meantime.

I know I have changed in myriad ways from the zealous elementary schooler and climate activist I once was – the movement and people that shaped me must follow suit. Whether you are at the 1997 stage – unaware or indifferent – or the 2015 stage – kicking and clawing – or fully in the present, we must make sure we are building a strong foundation for progress.