There is a magic to learning to love this world – not simply through our own lived experiences, but also by way of the stories that shape our perspectives. Heroes and damsels, verse and soliloquy – each narrative, fictional or not, is a subtle transformation of what we believe to be possible.

“Reading essentially was a big part of my childhood growing up, and it opened avenues that I did not perceive would open up for me,” English II teacher Erum Asif said. “When I was growing up, when I was reading, I thought I was wasting time, like I should be doing something academic. But later in life, when I was doing other subjects, I felt like I was better at science, at math, and maybe social studies and economics because I read a book about it somewhere.”

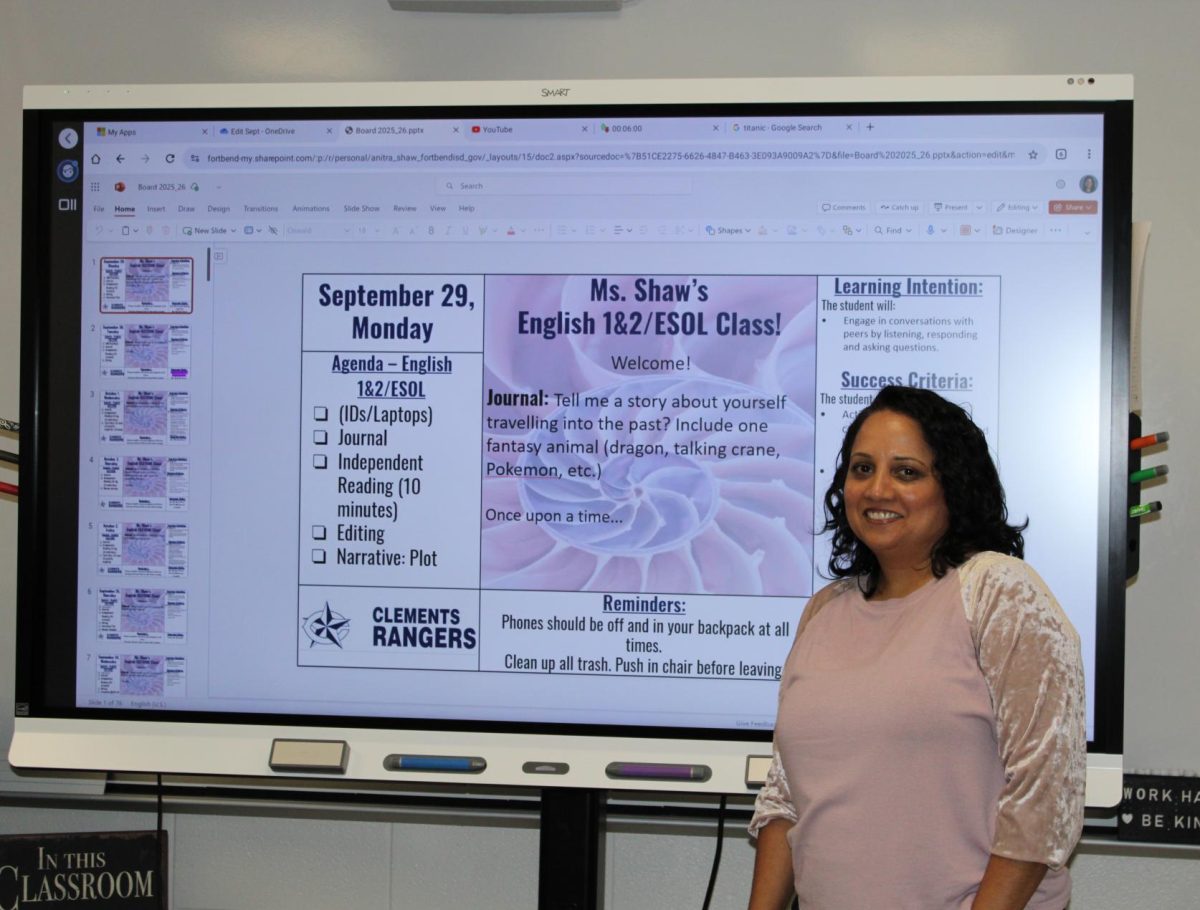

Asif is one of 18 English teachers at Clements whose love of reading morphed into a career dedicated to not only continuing her own passion for literature, but also passing on these crucial stories to the next generation.

“I tell my students, find that one thing that you’re passionate about and make a career out of it,” Asif said. “For me, reading was the something I was passionate about. If there was a job which had the attached description of just read all day and you’ll be paid for it, I would have signed up for that job. I think teaching was – because I get paid for reading with my classes—the closest thing I could find.”

There are the readers, like Asif, who from childhood form an intense bond with the written word and all the wondrous worlds that just 24 letters can piece together. There are also those whose journey is slightly more bumpy.

“When I was a kid, I didn’t like to read, which was really frustrating for my father, [so] he started paying me a dollar for a book,” AP English Language teacher Heather Hill said. “I was like ‘okay,’ and so I discovered ‘The Baby-Sitters Club’ and found that niche I liked.”

Eventually, Hill’s father – a teacher – told her that he couldn’t afford to keep paying her, but by that point, Hill said she didn’t care anymore.

“It’s like, ‘you don’t have to pay me’,” Hill said. “‘I’ll keep reading.’”

Hill started her career as a middle school English teacher, where she focused on teaching writing and grammar. Later, she transitioned to American Literature.

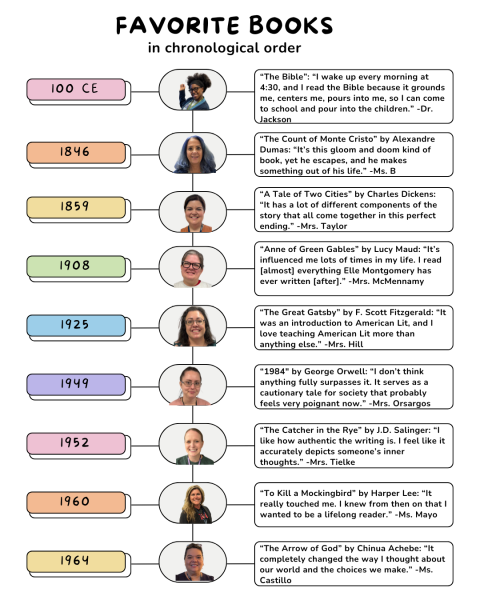

“I was very happy teaching that for a while,” Hill said. “It forced me to go back and read some books that I never actually had the chance to read in high school and college. I started to take on reading the books with the kids. Even though I’ve read them so many times, I see something new in it every time.”

Like Hill, AP English Language and Literature teacher Glenys McMennamy teaches “The Great Gatsby” to her students year after year — it’s a classic that is set in an era long past but nonetheless still resonates.

“These are the stories, the human problems we all deal with,” McMennamy said. “There are all these other parts of culture that I didn’t know and stories that are shaped by those cultures and those same human concerns. It’s beautiful.”

Although McMennamy now serves as the English department head, she didn’t feel “a magnetic pull” toward English early on. It was a major she settled for and only later thrived in.

“I didn’t realize other people didn’t find comfort and joy in it, so that made me feel like maybe this is what I need to be doing,” McMennamy said. “Maybe, this is my calling to have seen that.”

The beauty of high school English classes may partially lie in the great variety of students who sit down to read and be absorbed in the same story — who, in McMennamy’s words, find companionship and comfort in knowing that they are not “suffering alone” in an isolated world.

“I love the way that when students see themselves in literature, that it makes them come alive,” English I teacher Chriscia Jackson said. “Then when they’re able to write afterwards, they’re able to place themselves and see from another standpoint.”

Jackson operates without a set reading list. From social critiques to chick lit to science fiction, Jackson is reading 11 different books along with her students this year. In her own life, reading was an integral part of immigrating to the United States.

“Because we came from another country to here, reading opened my world up about American culture and then also beyond American culture,” Jackson said. “Once I started to read and learn new things, I was like, ‘Okay, I gotta go there. I want to see that.’ So reading just opened me up to all sorts of things.”

Beyond learning new perspectives, English I and III teacher Thomas Jouganatos credits reading for teaching him to think “outside the box”. Similarly, AP English Literature Regina Castillo is a firm believer in the transformative power of reading.

“If I’m reading something of value, it does have the potential to change the way that I see the world,” Castillo said.

Castillo’s love for literature was solidified in high school, while reading “Julius Caesar” by William Shakespeare.

“There was a scene where the public speakers said, ‘You blocks, you stones, you worthless and less than senseless beings,’” Castillo said. “I remember thinking, ‘that’s a really good insult.’ I kept reading it, the more I read it, the more I got into it. Then I didn’t need anyone to read it for me. I could do it by myself, and I enjoyed it.”

In everything, books are our eternal companions.

“I was one of those kids, where if I was forced to go to family friend events, I would bring books along with me and be in a corner reading,” AAC English II teacher Stephanie Yang said. “I’m definitely an introvert, so books have offered me an escape since I was young. Now, as an adult, I’ve kind of reignited my love for reading in the last couple years, since I finally got a kindle and started listening to audiobooks, so I’ve been able to enjoy a lot more books this way.”

AP English Literature teacher Brian Russow remembers sneaking a novel under his desk in class.

“As a kid, there was a lot of escapism in it,” Russow said. “Reading at night would relax me as well. Now, it’s more based on testing out or thinking about my personal philosophy, the way I look at the world.”

For many, reading is simply a way of life.

“We weren’t allowed to watch TV, so we just were always reading, going to the library and stuff like that,” AAC English I teacher Jackie Durio said. “So it’s just kind of the way I grew up.”

Dual credit English IV teacher Sarah Tielke has read every day since she was 5 years old.

“Reading has given me a lot of confidence, I would say,” Tielke said. “It’s definitely helped fill my mind when I don’t like to be surrounded by a lot of people.”

English teachers play an understated but deeply important role in the timeless passage of stories to the next generation, inspiring their students to not only explore reading and writing, but also become teachers themselves.

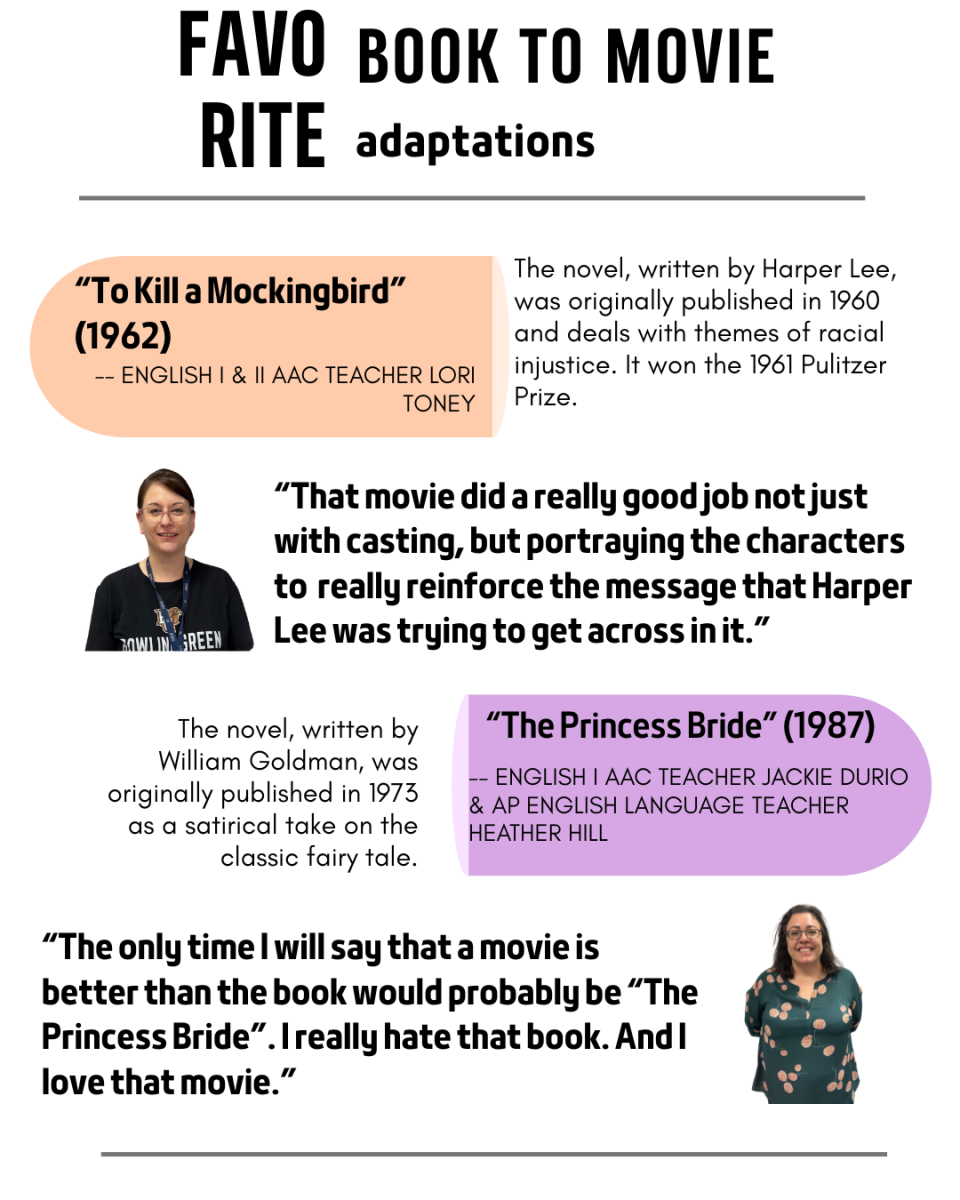

“I had an amazing teacher for both junior and senior year,” AAC English I & II Lori Toney said. “She was just such an inspiration. She loved literature so much, and I was already a bookish person, and she got me to read the classics that I thought were stuffy and awful, and she really inspired me to see them in a different light.”

AAC English II and AP English Language teacher Faith Orsargos also credits her decision to pursue a career in teaching English to a high school teacher, who used to be a businessman making six figures.

“He said ‘I realized that I had no joy in my career’,” Orsargos said. “‘I needed something that had more meaning.’ So I thought, why would I go the wrong route first and then seek meaning later?”

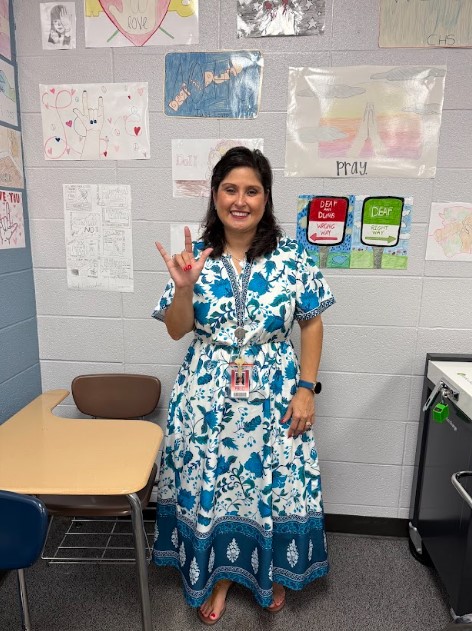

Orsargos majored in English and minored in education – she said she loved all of the courses that she was taking and didn’t feel the need to change course. In class after class, whether reading “The Princess Bride” with freshmen or analyzing “The Joy Luck Club” with sophomores, teaching English is a pursuit of the heart.

“I wanted to have an impact on others,” Toney said. “I wanted to share my love of reading and help them to have that same impact and help them to see the impact that books can have on their lives.”

For Toney, this impact is often clearest in terms of students’ skill development, especially vocabulary and critical thinking.

“Non-readers don’t have as big of a vocabulary or even just the critical thinking skills to think through the complexities of the situation,” Toney said. “Sometimes you read a book and you’re like, ‘oh my gosh, I’ve never thought of it like that.’ And you just spend all this time thinking about what happened in that book. They don’t have that experience.”

If reading is a form of observation, then writing is an act of transformation – bridging timeless tales with fresh ideas to create new worlds entirely.

“Especially because I like to write, reading obviously influences the way that you write and how well you can write,” English I teacher Hedaya Kelani said. “As you grow and morph and read different things, the way that you write and read and view things is going to be completely different.”

Assistant principal Ashli Taylor has loved writing since she was in high school, competing in UIL writing events – Taylor was the English department head prior to becoming an assistant principal.

“I think that there’s so much to English that makes it fun,” Taylor said. “Analyzing literature, writing, and all the things that go with that are just fun to teach.”

English III James Rumely said that part of the appeal of teaching English was the “engaging” nature of the job – it’s multifaceted and ever-evolving as the literary landscape changes.

“ I didn’t feel like I was constantly being bored all day while I was doing it,” Rumley said. “I liked literature.”

The name ‘teacher’, in truth, disguises so much more – although many English teachers are readers, they are also poets, creative writers, and above all, dreamers. Kelani, for instance, is a published poet and has written several children’s books pending publication.

“I always tell my own students, you should take risks [and] do things that bring you joy,” Kelani said. “Then hopefully, you’ll get somewhere.”

There is an aspect of reading that is deeply uplifting – for the underdog or anyone new to the world of literature, stories represent possibility when in real life hope is lacking.

“My childhood wasn’t the easiest growing up, and so reading was my escape,” English II teacher Lynson Alexander said. “That’s still something that even as an adult, I still enjoy about reading, how it just envelops you into this completely other space. I don’t think any other form of entertainment can do quite like a book.”

Before librarian Marion Brennan became a librarian, she worked as a reading specialist – for Brennan, success is as simple as getting books into kids’ hands.

“I would always help kids that couldn’t read or had great difficulty in reading and I have such a passion for books that I wanted to help them become readers,” Brennan said. “I was at McAuliffe, where many kids – it’s a Title I school – don’t have running water or electricity. It depends on how much money they have. Many of my kids when I was there, they never had books because books are a luxury.”

Accessibility is a perpetual barrier to reading – English IV teacher Fay Mayo, who didn’t enjoy reading as a kid, said that she probably would have been diagnosed as dyslexic.

“I self-taught the tools needed to get over that,” Mayo said. “I think that being a struggling reader and then now loving to read makes me love to read more and also makes me want to help kids that hate reading because I know if they could just find that one book, it would capture their heart and they would be lifelong readers.”