As an only child, Senior Abby Zhao says social connection is really important for her.

“I feel loneliness pretty much on a daily basis, I would say, because my family’s really small,” Zhao said. “So I don’t have that kind of social connection at home, in terms of sibling connections.”

Zhao calls feeling lonely a “pretty universal human experience” – her strongest memory of feeling isolated is at church, where she joined a longstanding community as a relative newcomer.

“They’ve been friends since they were in elementary school and they just stayed in the church,” Zhao said. “As someone who recently joined the church, it was hard to fit into their dynamic with each other. It was hard to understand how they know each other and how they behave with each other, so obviously you feel a little bit isolated.”

In 2023, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy released a report called “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation”, calling loneliness and isolation “profound threats to our health and well-being”. In a culture constantly pushing for bigger and better, Zhao said the quality of relationships has taken a backseat to quantity.

“Nowadays, it’s hard to tell that we’re in a loneliness epidemic because there’s social media and it feels like everyone is connected to each other a lot more,” Zhao said. “But at the same time, I do think that the quality of these relationships probably has gone down, at least in my experience from elementary school and from observing other people.”

The interactions taking place online are, in Zhao’s opinion, less genuine.

“For example, when someone tells you a joke that I don’t find funny at all, I would still comment ‘LMAO’ even though there’s no way in a million years I would ever laugh at that joke,” Zhao said. “Sometimes I’m talking to ten people at once on Instagram and I type one message, wait for them to respond, and go to another message. People on social media are a lot less engaged.”

Zhao isn’t immune to the allure of social media or video games, but she’s also found a far more creative way to fill her alone time: hiking. At night, when her family is asleep and Zhao starts to feel lonely, she’ll walk the trails at Memorial or Brazos Park.

“When you hike, you’re not looking at your phone because you have to pay attention to the road,” Zhao said. “You have a lot of time to really reflect on things, and then the scenery is really nice, so it kind of takes your mind off of school or your social life.”

At school, Zhao said her friends have functioned as a support system.

“We kind of share our problems with each other,” Zhao said. “Although sometimes they can’t directly help me, by listening to my problems, it really helps me see that I’m not alone emotionally. Everyone has their own struggles.”

Zhao has also found community in different student organizations on campus, some more so than others – she said she isn’t quite passionate enough to be a part of the orchestra community or studious enough to be in the more academically-oriented study communities. There has been one place where Zhao feels like she fits in, though: martial arts.

“Those communities are just welcome to people in general and are usually really positive,” Zhao said. “Everyone is on their fitness journey, everyone’s on a different stage, and they’re pretty inclusive.”

Ultimately, though, if late-night hikes have taught Zhao anything, it’s the value of solitary activity.

“You don’t have to always be in someone else’s company,” Zhao said. “You can just really enjoy your own company. It’s good to feel independent.”

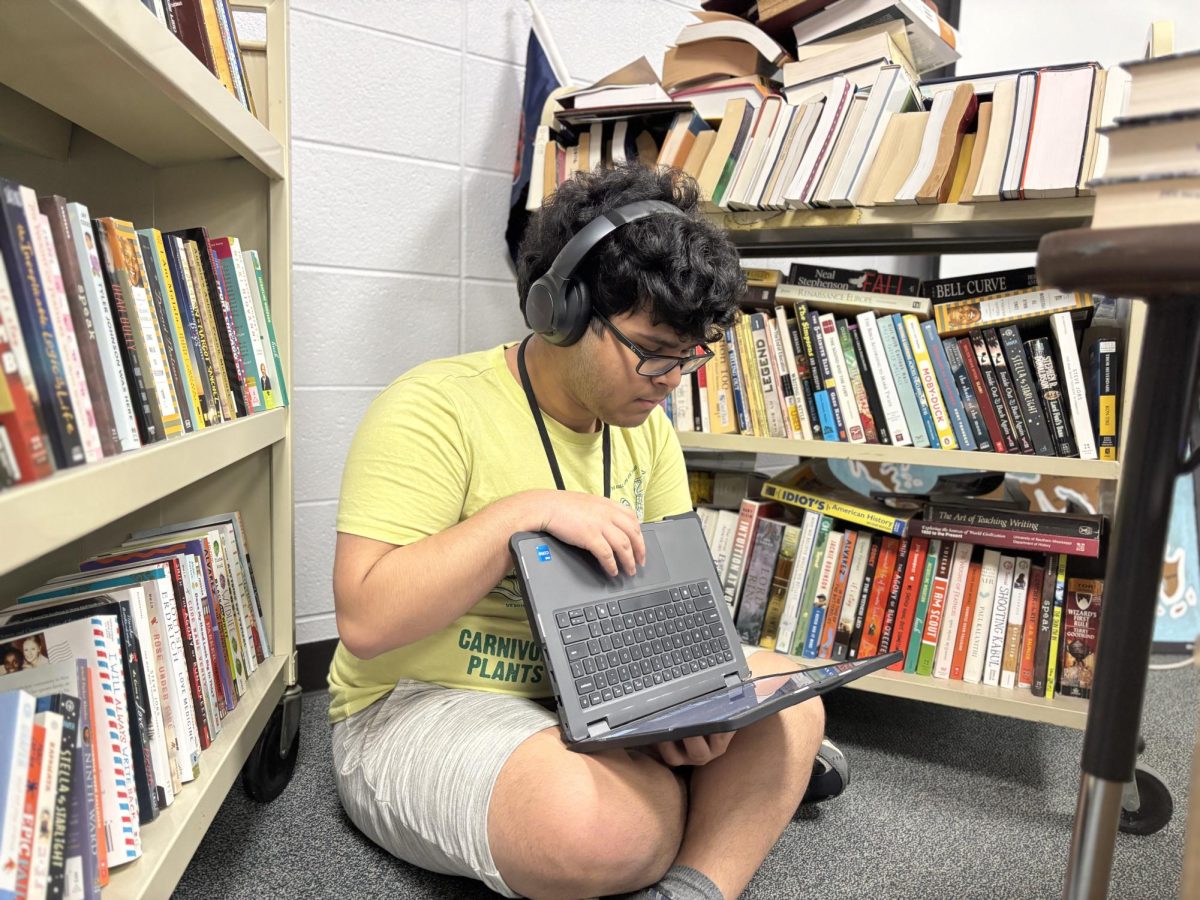

Senior Justin Xu is used to being the new kid.

“I moved during COVID, between 7th and 8th grade, [and] when I moved there, it was online [so] I had no one to talk to,” Xu said. “There was no one to talk to, period. After that, I immediately went to high school where everyone was new. It was a lot better. When I moved to Boston, it was also right before kindergarten, so it was all new faces.”

In the process of moving around, Xu said he’s learned to be content with being alone. Friendships tend to unfold “organically”, in Xu’s words, rather than result from Xu actively introducing himself to new people, which he said he’s too awkward for.

“To be honest, I feel like making friends is just like we start talking and then we’re friends,” Xu said. “I never identify a friendship so much. We never say, ‘oh, we’re friends now.’ I feel like we just eventually get closer and start talking more, and go close that way.”

Xu is skeptical of the idea that a loneliness epidemic exists. Although he may not be talking to the people around him when he’s engrossed in a game, Xu said he feels comfortable messaging a friend when he wants to, or not reaching out when he doesn’t feel like it.

“I’d say [social interactions] are definitely important,” Xu said. “They’re important, but it’s not like if I don’t have social interaction for one day, I’m going to be breaking down.”

Depending on his mood, Xu does one of two things when lonely: text a friend or start playing games.

“I feel like if I do experience [loneliness], I usually just push it to the back of my mind,” Xu said. “It’s not really something I bring up and dwell on, like, ‘oh my god, I’m lonely.’ I’d rather just go online and start playing games.”

In Xu’s opinion, the loneliness epidemic is the product of an overly cynical society. If there is an epidemic to fix, Xu said he thinks technology has to be part of the solution.

“Just adapting with the technology and making more connections in new ways, I feel like that is something that would probably happen eventually,” Xu said. “Obviously, with the advent of technology, a lot more conversations and stuff are online. There’s people going home, doing meetings online. Everything is connected through the internet, so I feel like people will eventually adapt to that and make friends that way if not the traditional way that most people think.”

Even so, Xu isn’t a fan of purely virtual friendships. If there’s anything he’s learned from being the new kid, time and time again, it’s that the first step is always the hardest – just reaching out to someone and saying ‘hi’.

“Once you do that, I feel like it’s a lot easier and things just come along very easily,” Xu said. “So saying hi to someone for the first time, when you sit down in front of the lecture hall, I feel like it’s a great way to make close friendships. Introducing yourself to new people, a lot of people, is also something I would definitely recommend because some people have different viewpoints and different things they like, and you don’t know that when you first sit down next to them.”

Senior Grace Tan is a self-described “people person”.

Two months ago, when Tan saw a foreign exchange student from Germany sitting in her usual lunch spot, she immediately struck up a conversation.

“He was just sitting there eating, and I was like, bro, he’s from Germany, that’s so cool and interesting,” Tan said. “So I started talking to him, and it just went from there.”

They talked about books together, and the exchange student quizzed Tan on her knowledge of German cities. For Tan, getting to know people just for fun is “really rewarding”.

“There’s just so much to learn about other people,” Tan said. “I think it’s a waste to just stick to the same old people. Obviously, people are naturally gravitated towards people from a similar background, similar ethnicity, similar culture. That’s only normal. But I think life would be much more interesting if you talk to people from other walks of life.”

And it’s not just strangers, either. For Tan, friends, family, and any sort of good company are important and necessary parts of life for any person.

“You need people around you to support you,” Tan said. “I think if I was alone throughout high school, like, that would have been really hard. Obviously, I have parental support, but you need people your age who are going through the same thing to completely understand your challenges and things that you’re going through.”

For Tan, friendships provide both academic and emotional benefits. Academically, it is often as simple as explaining a difficult concept to a friend. Emotionally, friends can be a supportive sounding board for the uncertainties of adolescence.

“When you progress in your friendship and you have certain worries about your life, like, ‘oh, I’m not sure about my future,’ because everybody’s stressed about their future in high school, that’s when, if your friendship is at that level, you can discuss those worries with them,” Tan said. “And it feels like, when someone else is going through the same thing, you feel not alone anymore.”

Tan and her friends have a tradition of making “calls for no reason”.

“It’s not like ‘oh, let’s have a physics study call,’” Tan said. “It’s nothing like that. It’s more like you call just to call. We don’t have to talk. As long as your presence is there, it’s enough.”

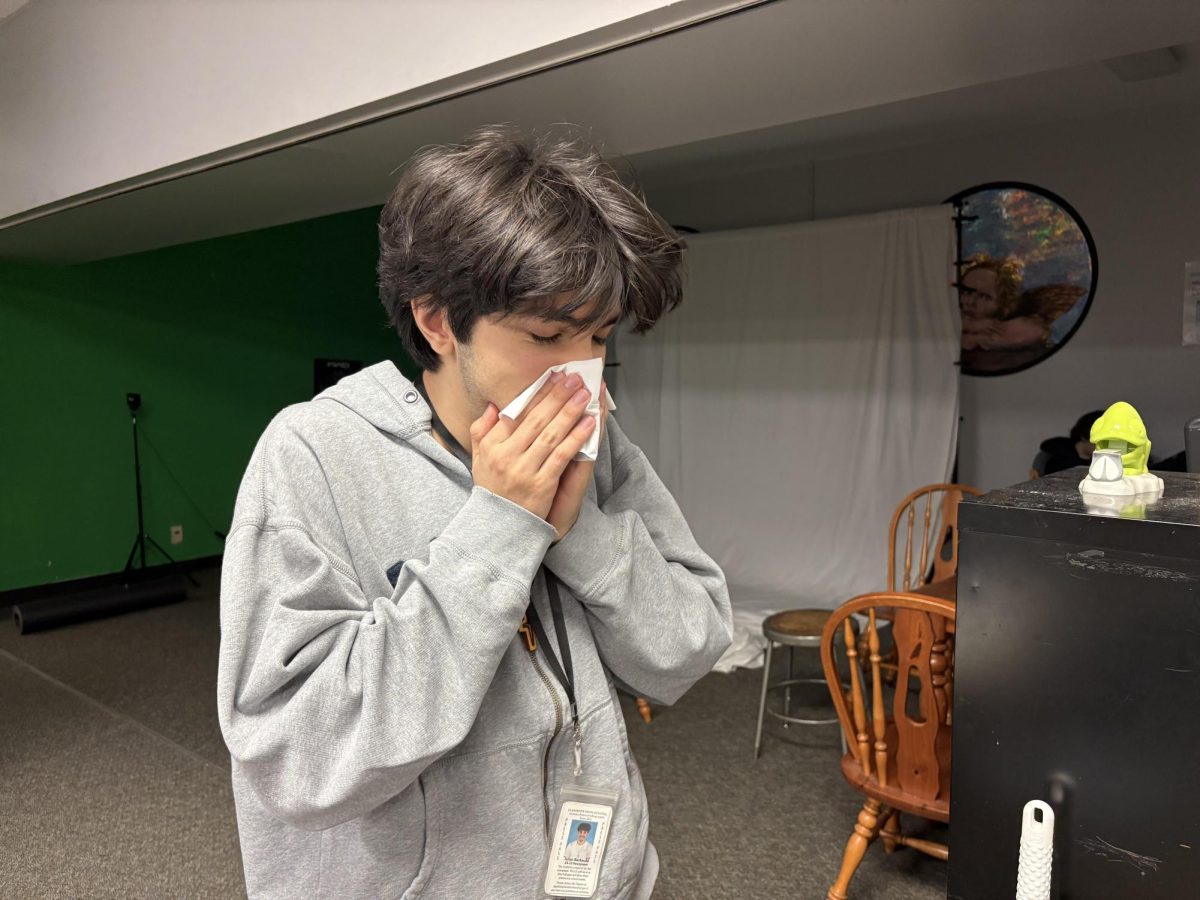

Tan also has a twin brother and a younger sister, and supportive parents. In spite of the people there for her in her life, though, Tan said loneliness is unavoidable.

“In COVID, I got really, really used to just being by myself and being online all of the time,” Tan said. “That transition from freshman year was a little bit rough because you’re in a new high school and [with] new people, and I’d gotten used to being by myself.”

Research shows that loneliness and social isolation among children and adolescents increase the risk of depression and anxiety. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, which virtually eliminated in-person social connections, social isolation was on the rise – on average, from 2003 to 2020, social isolation increased by 24 hours a month. Tan thinks social media is part of the problem.

“I think [social media] kind of manipulates the way people view socializing,” Tan said. “Because if you could easily just DM someone or message someone on Discord, it may decrease the incentive to reach out to a person in person.”

Even as a confident and capable extrovert, Tan acknowledges that passive scrolling is a lot easier than making the first move to talk to someone in real life – her best advice is to just “bite the bullet”.

“I think the mindset that helped me is if you’re in a new place, most likely there’s going to be other people who’s in a similar position,” Tan said. “So I think mustering up the courage and confidence, building up yourself first, and then reaching out is the best way.”

Tan starts simple. If someone is sitting alone, for instance, she’ll ask if they’re normally in A lunch or B lunch – something “really casual”.

“Then you can go ahead and say, ‘oh, what grade are you in?’” Tan said. “And then go from there and be like, ‘oh, you’re a junior. You must have a lot of AP classes.’ I normally talk about something that I may have a lot of knowledge about, and I know that they may have a lot of knowledge about. When you’re on that same playing field, you have a way to bounce back and forth and have a conversation.”

One conversation may not end the loneliness epidemic, Tan knows, but she is persistent in reaching out.

“Maybe you’ll finish the conversation and never talk again – maybe that’s just because you didn’t have that spark,” Tan said. “That’s completely normal, [but] I think most people would appreciate you having a conversation with them.”

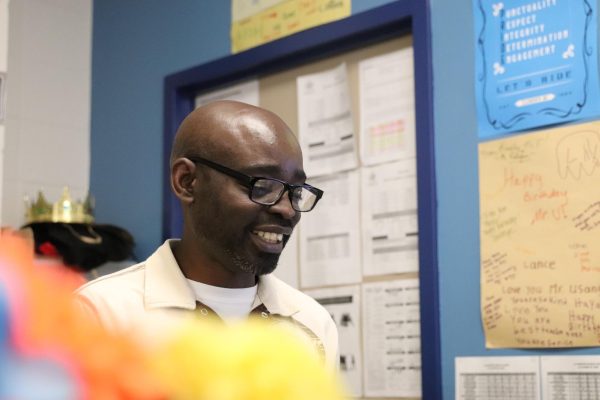

In SAILS teacher Enobong Usanga’s classroom, communication is everything.

“They always say in special ed, if it’s not written down, it didn’t happen,” Usanga said. “For example, if I have a talk with one of my parents and say, ‘Hey, John Doe did so-and-so’, they will ask me, ‘let me see, show me data.’ If I can’t show them something, then that thing didn’t happen. So it doesn’t matter how big or small it is, we’ve got to document, document, document, document.”

Usanga is also constantly talking with the three other SAILS teachers to make sure he’s on the same page with them. He covers English and reading, somebody else teaches math and science, and still somebody else does social studies – all of them have to collaborate to make sure the students’ learning is progressing smoothly.

“We have to connect socially, academically, behaviorally, to get this job done most effectively,” Usanga said. “As a person, I think communication is a big factor in anything we do.”

Although SAILS is a small department, and the number of students that Usanga is personally responsible for is small, Usanga is nonetheless a well-known presence around campus. Students, co-workers, and administrators alike can all count on a wave and cheerful greeting from Usanga, known affectionately as ‘Mr. U’.

“I made a choice a long time ago: I can either be happy or sad, I can either cry or laugh,” Usanga said. “You know the obvious answer to that, what I chose. It’s very intentional. I focus every single day to make sure I’m on that path of being happy, being glad to be here, being blessed to be here.”

Those social connections, even just a ‘Hi, how was your weekend?’, are Usanga’s way of demonstrating care. Especially as a SAILS teacher, Usanga works to make sure his classroom is a place where students can sit down and feel safe.

“It’s the way you deliver, the way you teach, the way you approach them, the way you care, [and] your empathy,” Usanga said. “I always say to my colleagues, everyone in my classroom can see right through you as a teacher. I’m very transparent. You can’t fake nothing. They can know exactly who really cares for them, who really likes them, who really goes back for them.”

The work, Usanga said, is challenging but rewarding. He has to differentiate his instruction to manage what he calls “different moving parts”, from teaching entirely non-verbal students to high social kids. To tackle his never-ending to-do list, Usanga starts the day at 3 in the morning.

“I’m in this classroom all by myself,” Usanga said. “There’s no distraction[s], [so] I can get my work done now. If I have to get my work done in an empty classroom, I’m not really lonely, I’m just doing what I gotta do to get my work done.”

For Usanga, paperwork occupies the solitary moments where otherwise, loneliness might intrude. Usanga is also hesitant to call his students ‘lonely’.

“Some of these kids don’t really know,” Usanga said. “If you don’t know what’s out there, then you don’t really know, and you can’t really miss it. Some of these kids are at home all day every day, in their bedrooms, in their house, they hardly go anywhere. So if you don’t know what’s out there, there’s nothing to miss.”

There are ways for special ed students to get engaged socially, but there’s typically little overlap with traditional school activities that tend to be loud, rowdy, and potentially overstimulating. For instance, Usanga arranges a special prom for his students as an alternative to the actual school dance.

“[Special prom is] geared towards just our kids, our community, and everyone’s involved, even our alumni are welcome, parents are welcome,” Usanga said. “We give them a sense of what’s happening out there, even though they can’t really be out there to enjoy that, or to be in that.”

At the end of the day, it’s Usanga’s work that gives him a sense of purpose – small, incremental hints of progress in his students keep him coming back. The kids, he said, keep him too busy to be lonely.

“For me as a special ed teacher, it’s the little things that makes me keep going, that propels me, that drives the boat,” Usanga said. “If my kid can open a bottle by himself but couldn’t do it before, if a kid can button a shirt but couldn’t do it before, if a kid can wash their hands properly for 20 seconds or so but couldn’t do it before, because I’ve had that time to invest in them and teach them those skills, and now they can do it – that makes my day. That makes me keep doing what I’m doing.”

Usanga calls his class the “world’s best class”. It’s there that he pushes his students to achieve their highest potential; he said he wants the whole world to know that the sky’s the limit for kids with disabilities.

“My role here as a teacher and educator is just having a voice for someone that doesn’t have a voice – being their voice, basically,” Usanga said. “The world has to know that just because you are autistic or you have Down syndrome or because you’re a special needs kid doesn’t mean that you can’t do so much.”

Social studies teacher Tara McMartin thinks about her daughter every day.

“You have those teen years where moms and daughters really clash big time and then they grow up and they go to college and they realize that mom’s not the enemy and mom can actually be your best friend,” McMartin said. “We were kind of reaching that point and I lost her at a really, really pivotal point in her development. It is lonely without her.”

At the memorial service, McMartin said it was “heartwarming” to see how many people came out to testify to the positive impact her daughter had – in elementary school, for instance, McMartin’s daughter was the only kid who would play with a new student. That student later wrote a book in honor of McMartin’s daughter.

“You find out how much just a person can affect other people, what a positive impact they can have on other people,” McMartin said. “That makes you realize that every interaction you have with someone else, you can change someone’s life just by being in their life.”

The outsize impact of one exchange, whether positive or negative, is an idea that McMartin brings into her classroom.

“There have been times where I’ve actually apologized, like ‘hey, maybe that came off wrong,’” McMartin said. “I don’t want to be the teacher that that person remembers the day that their teacher went off on them for no good reason. You have to stop sometimes to remember, is that going to be something that’s going to impact them negatively for the rest of their lives?”

McMartin said her classroom functions best when students feel are willing to communicate with each other and take the risk of speaking up from time to time.

“The classroom should function like a small community group where a person feels comfortable and a part of the action,” McMartin said. “If they don’t feel that, then not only does it hurt the student, but it breaks down the classroom feel and success of the lesson.”

Social connection, in McMartin’s words, helps “break down barriers”, establishing safety, security, and respect. Now, though, McMartin said it’s become too easy for students to use electronics as a safe way to avoid talking with other people.

“It’s become more socially acceptable not to connect,” McMartin said. “Before we had our best friend in our pocket – our phone – we had to talk to each other. You went into a class and it was weird and awkward to just sit there and not communicate with someone. But now people, when they’re not feeling safe or they’re feeling shy, they just kind of stare at their phone and pretend they’re doing something important.”

Discussions and open-ended questions can help break through to reluctant students, but McMartin acknowledges that “teachers have bad days too”. Following her daughter’s death, she said she’s had to actively put in the effort to make social appointments in her own life.

“Whether it’s a service community or a faith community, you have to make an effort to go out and seek people,” McMartin said. “Even as an adult, I think a lot of us are so busy, sometimes we just want to go home and relax and be quiet and have that down time, because we’re stimulated all day long, especially in the school setting. But you have to make an effort to make the lunch date with your friends that you haven’t seen forever.”

McMartin sponsors the Interact Club, a service organization; whether by meetings for events over the weekend or organizing community activities, McMartin said volunteering is a good way to get people out of their shells.

“You can show up to a service event and no one knows anybody but you’re all there for a common purpose,” McMartin said. “Then, you get to know people [and] you work together for good. After you bring people together, you see the positive impact it has.”

Even as a self-described “extroverted introvert” who enjoys having downtime, McMartin said she needs social relations – and so does everybody else.

“I need the friendships [and] I think everyone needs friendships,” McMartin said. “We’re not meant to be individuals alone in the world. We’re meant to be in community with each other.”

Eno Usanga • Apr 23, 2025 at 1:20 pm The RoundUp Pick

Karen this article is simply outstanding. Not because I was featured in it but the level of professionalism and attention to detail is amazing. Keep up the good work and keep writing. I’m cheering you on every step of the way.