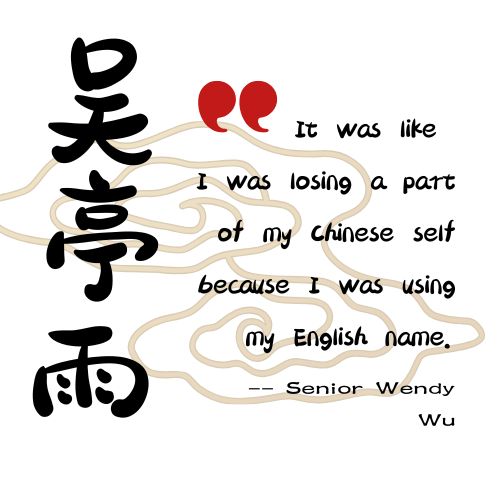

吴 (Wu): family name.

吴 (Wu): family name.

亭 (Ting): stop.

雨 (Yu): rain.

Senior Tingyu Wu’s name is an homage to her Chinese heritage. But to most of her friends and classmates, she’s known as Wendy, a name she started using when she moved to America as a child.

“When I introduced myself with my English name, it was much easier for other people to remember me,” Wu said. “It was much harder for even teachers and students to remember my Chinese name, so I just said it in English.”

Adopting an English name is something of a rite of passage. Often, it’s simply the practical thing to do – trading foreign syllables for more familiar combinations of vowels and consonants makes class roll call easier. For the sake of convenience, first- and even second-generation Chinese immigrants bid goodbye to the sentiments, hopes, and dreams carried in their given names.

“[My English name] made me feel more Americanized,” Wu said. “It was like I was losing a part of my Chinese self, because I was using my English name, and then my parents were encouraging me to, like, use English more. Over time, as I got into, like, fourth and fifth grade, I realized I was losing my Chinese language.”

From there, Wu said it was a “slippery slope” – she said she forgot a lot of Chinese words, and even her parents use her English name now. At the grocery store, they’ll call “Wendy, 你在哪儿?” Not Tingyu, but: Wendy, where are you?

“I remember when I visited China in middle school, when people asked for my name, it’s difficult to answer the question,” Wu said. “Because in America, I’m always so used to being like, ‘oh, my name is Wendy.’ But in China, I would just introduce myself with my Chinese name. Hearing other people calling me that is sometimes kind of foreign because most people don’t call me that.”

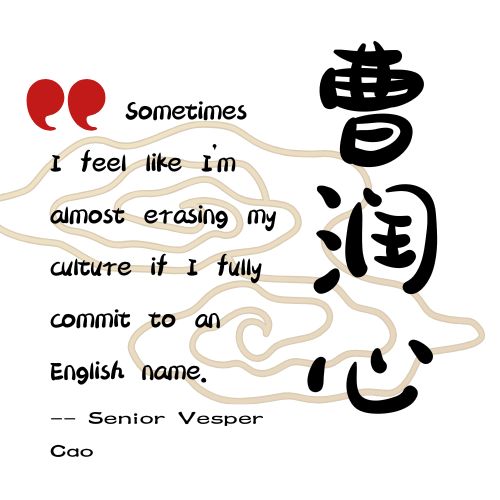

Senior Runxin Cao has gone by the name “Vesper”, and said she also feels a sense of detachment from her culture. Her parents, often busy working, didn’t have time to teach her when she was growing up. In the future, Cao is tentatively planning to use her English name more.

Senior Runxin Cao has gone by the name “Vesper”, and said she also feels a sense of detachment from her culture. Her parents, often busy working, didn’t have time to teach her when she was growing up. In the future, Cao is tentatively planning to use her English name more.

“I’m trying to get my citizen[ship] and I’m like I should probably change it to a English name,” Cao said. “Also, I’ve heard looking for jobs is easier if you don’t have a foreign name. It’s just like a slightly difficult position where I don’t really know how to feel about it.”

Cao describes this name dilemma as a “cultural identity crisis” – on the one hand, it’s useful to be seen as more American. On the other hand, her Chinese name is a part of not just her culture, but her parents’, too.

“Especially if it’s a new language [for my parents], sometimes I feel like I’m almost erasing my culture if I fully commit to an English name,” Cao said. “I don’t know what I should do about that feeling because it’s just hard.”

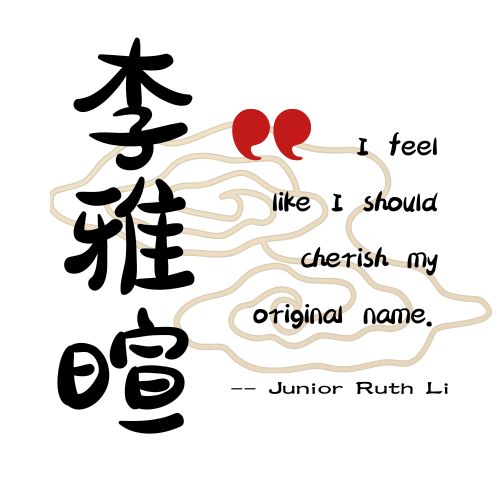

李 (Li): family name.

李 (Li): family name.

雅 (Ya): elegant.

暄 (Xuan): first sunrise in the winter.

Yaxuan Li is “Ruth” to most who know her. Back in middle school, Li said she was more comfortable with her English name, but she changed her mind after coming to Clements, where over half of the student body is Asian.

“It’s more diverse, and I feel like I should cherish my original name,” Li said.

Li described it as an “awkward phase” when her Chinese friends were calling her Yaxuan but her English-speaking friends would call her Ruth. Although having an English name made things easier, it also felt incohesive.

“I’m more introvert[ed] when I’m introducing people that I’m Ruth, rather than Yaxuan,” Li said. “I’m more confident with my overall Chinese identity and the language itself. I’m actually planning to use my Chinese name only for the future, because that’s just what I was born with, right?”

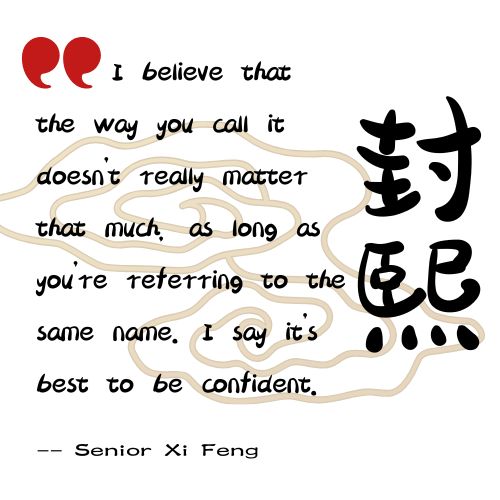

Senior Xi Feng uses a similar approach – although he picked an English name (Kevin), he didn’t use it for long. Now, he tells people who can’t pronounce “Xi” to call him “Z”.

“I believe that the way you call it doesn’t really matter that much, as long as you’re referring to the same name,” Feng said. “I say it’s best to be confident.”

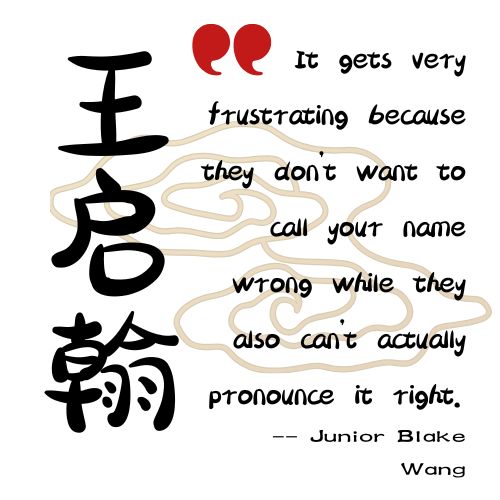

王 (Wang): family name.

启 (Qi): inspire.

翰 (Han): knowledge.

Junior Qihan Wang’s first English name was Pluto, after the cartoon dog in Mickey Mouse Clubhouse.

“Then, I had an English teacher when I was in kindergarten, so she thought that it was a weird name,” Wang said. “I thought that Blake might sound a bit similar to Pluto, and then I just went by Blake.”

Wang started using his English name from the first moment he arrived in America, since his actual name is difficult for native English speakers to pronounce – he said he thought Blake would be more welcoming.

“I think it’s better to pick a new name because it’s more friendlier for people here that would likely be your friends,” Wang said. “They’re trying to welcome you to their groups but then whenever they want to call you by something, your name is very hard to pronounce for them. It gets very frustrating because they don’t want to call your name wrong while they also can’t actually pronounce it right.”

For Wu, though, the lines are more blurred. Even though she’s gone by Wendy for years, Wu has started using ‘Tingyu’ in professional settings.

“I would introduce myself as Tingyu for interviews or even writing emails,” Wu said. “My email address is [email protected] [because] when I set that email, I was in third grade, and I wanted to use my English name. But now when I send emails, at the end, I’m like ‘sincerely, Tingyu Wu’.”

Wu said she is trying to integrate the name ‘Tingyu’ into her life more, but it’s a difficult balance to strike.

“I still remember in fourth or fifth grade yearbooks, they have your name under [your picture] and I remember my teachers used to ask me, ‘okay, what do you want your name to be in the yearbook?’” Wu said. “My dad wants my Chinese name. My mom is like whatever you want. And for me, both names are part of my identity so I used to just write it as Tingyu (Wendy) Wu.”

It didn’t stop there. In middle school competitions, only one name was allowed – Wu used ‘Wendy’. But when she visited China, she introduced herself with her Chinese name – Wu said she had to remember that “oh, yeah, I still have that Chinese part of me”. More recently, when Wu got a varsity jacket, she again had to decide what name to use.

“I was like, ‘well, I don’t know’,” Wu said. “So what I ended up deciding was in the front, I put Tingyu, and then in the back, with my last name, I put Wendy with it. I want to use both of them.”

After countless awkward mispronunciations and years of wanting to fit in with all the other kids, Wu has one piece of advice for others with similarly unpronounceable names.

“Just embrace it,” Wu said. “You have two names. You’re unique. They’re both part of who you are, and you shouldn’t degrade one of the names just because you feel other people can’t pronounce it. They’re both who you are.”