In classrooms across the world, artificial intelligence is no longer a futuristic concept—it’s a tool that’s transforming how students learn, how teachers teach, and how education evolves. From personalized lessons to real-time feedback, AI is reshaping the classroom experience, raising questions about the future of education and the role technology will play in shaping the next generation of learners.

The previous statements may seem sufficient enough for the introduction to a news article about the use of artificial intelligence in schools — aside from the fact that it was completely written by generative AI.

Demonstrated above is one of the obstacles teachers encounter when assessing students’ work: differentiating students’ work from that of generative AI. AI is everywhere: the news, social media, art pieces, and now even in school. Although not all teachers or students use AI, the majority are aware of its gradual presence in the education system. To adapt to their changing environment, students and teachers have cautiously integrated AI into their day to day classroom activities, despite variance in opinions about the extent of AI usage in classrooms and its impact on students’ cognitive development.

Over the past year, student usage of AI in schools by students has increased from 58% to 70%, and AI usage by teachers has increased from 51% to 67% only over the past year. For many teachers, their student’s use of AI has complicated their grading process.

“We were already kind of up against a wall with the internet and plagiarism in general, and now this is a whole new ballgame,” AP English Language and English II AAC teacher Faith Orsargos said.

Teachers are aware of the academic pressure most students face especially in work intensive classes — primarily because students are attracted to the convenience of AI applications.

“I know that I am an adult, and I know how to use it responsibly, but I know that my students are not,” Orsargos said. “As an overwhelmed academic adolescent, they’re going to do anything they can to avoid all of the avid pressure, and if that means using AI to do stuff for them, they will.”

The growing presence of AI has troubled teachers, as its constant evolution requires educators to adapt to the changing environment.

“It’s really impossible to mitigate fully,” Orsargos said. “I remember when Schoology was rolled out, there was the whole concept of doing Schoology discussions, and [students] loved them so much. Giving these students the ability to have academic discussions with each other, and now, last year, it was so easily discernible when students used AI to generate their responses, because they would use vocabulary words they didn’t know, and it does interfere a bit.”

Due to these recent changes, teachers have begun to worry about the negative effects the constant use of AI have on their student’s learning.

“If you give yourself the chance to let, whether it be AI or even another person, have a thought before you have the thought yourself, you’re gonna end up not having the thought yourself,” Orsargos said.

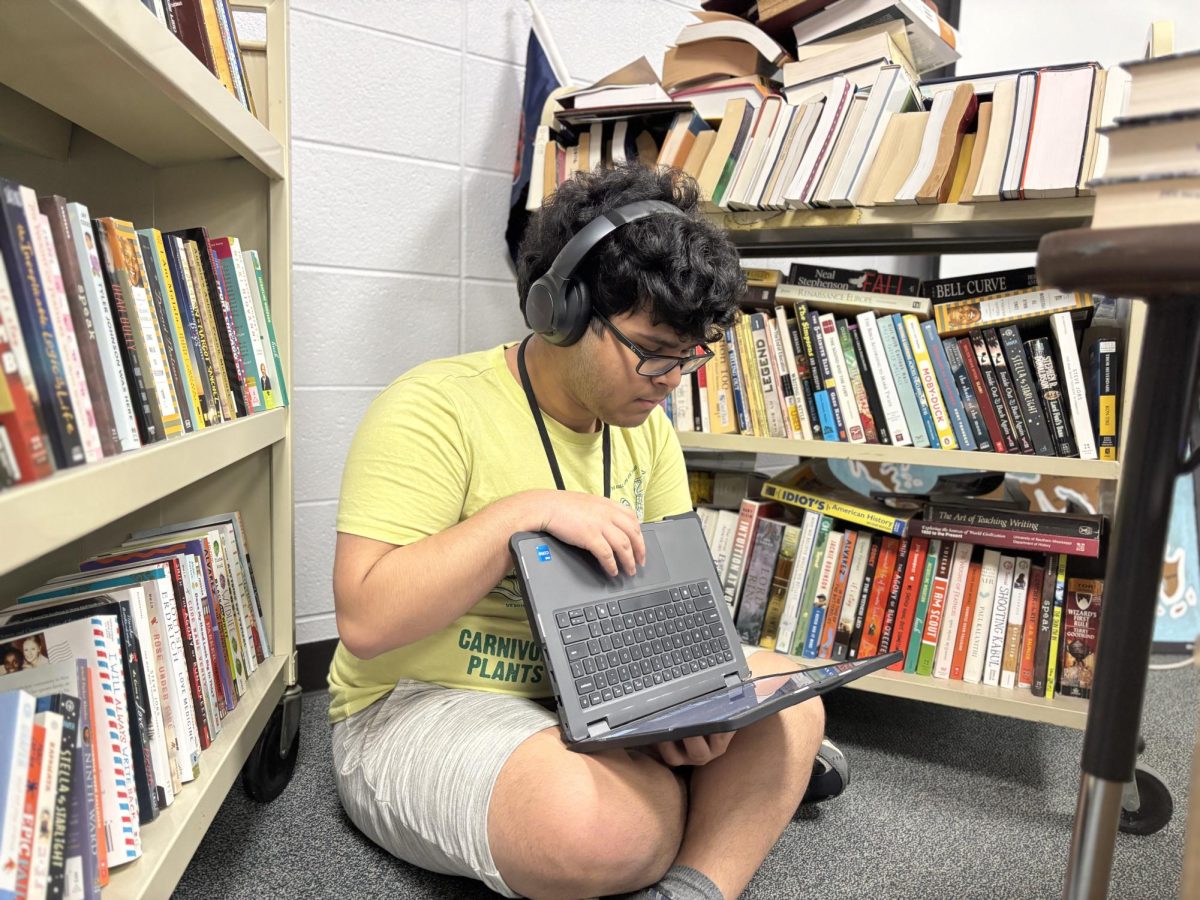

Despite using AI themselves, many students share similar sentiments; while some are drawn to AI because of its convenience, they also feel that AI takes away from their own learning and cognitive development.

“You’re just asking someone to do your work for you, and it doesn’t allow you to think,” one senior, who requested to remain anonymous, said. “When you’re so used to having someone do something for you, when you find yourself in a situation where you don’t have that leverage to back you up, you’re just going to fall.”

Though students might be using AI on a weekly basis primarily for studying purposes, there can be a sense of dissatisfaction with their own use of AI — they feel as though there are times they have to rely on AI to learn the content, particularly in higher level math and science classes.

“I use stuff like Photomath and Mathway often, but only during math,” one junior, who requested to remain anonymous, said. “You don’t learn anything from it. I don’t retain the information as well due to me using Photomath for things I’m not familiar with.”

These traits in AI applications take away from students’ learning experience. Because of this, Orsargos stresses the importance of only using AI for topics students have already mastered.

“If you use AI in a thing that you’re not knowledgeable about, you’re really running the risk of it being completely wrong, and you’re just slapping your name on it,” Orsargos said. “So then you’re avoiding learning, but you’re also putting something, and you’re potentially turning something in that’s also inaccurate.”

In spite of its drawbacks, teachers continue to try to utilize AI as a learning tool in the classroom. Just this year English II and III classes have started using Class Companion, a learning AI application that grades student’s writing and provides feedback based on an uploadable rubric.

“I think it’s really helpful,” Orsargos said. “Students care so much about their grades. They care so much about their performance, and this is a chance for them to be able to see ample rounds of practice writing with feedback, whereas a teacher can’t really do that fully over and over again.”

Although Class Companion can serve as a valuable resource to students and teachers, Orsargos admits, like any AI application, it has its flaws.

“I try to make my feedback personal and easy to digest, and I feel like the AI will say something … and then it’s not going to give any suggestions for what they could have done differently,” Orsargos said. “I don’t think it’s better than human feedback, and I think that if we try to push it as if it can replace human feedback, then humans might stop giving feedback.”

In different disciplines, though, it could be argued that adapting to the presence of AI goes beyond stressing its weaknesses and involves understanding and teaching students how to utilize it to its proper extent.

“If we don’t use it and teach how to use it appropriately, then it will be used inappropriately,” Physics I and AP Physics I teacher C. Brice Turner said. “If we’re not monitoring how it’s being used and we don’t become familiar with it, then we won’t be able to tell when it’s being used improperly.”

Turner said that there is a fine line between using AI as a tool and using it to avoid putting in effort at the expense of students.

“There are times when students become complacent and they rely too heavily on something like [ChatGPT], and they don’t do the due diligence of checking to make sure that what it did was correct, that it really makes sense, or that they’re actually still learning the content,” Turner said. “Because at the end of the day, what matters is: what do they learn?”

Turner believes that AI should be a prominent presence in his classroom as long as it is being used the right way. He argues that having AI can assist students while trying to learn a new concept or generate ideas for activities, but it does not replace a student’s understanding of the topic and their schoolwork.

“Heck, have [AI] write the whole thing for you if you want, as long as you’re going back and looking at what’s been done and you’re verifying it and you’re vetting the sources that it’s using,” Turner said. “If you get something wrong at that point, then you need a lot more help than ChatGPT can give you.”

Both Turner and Orsargos express that school and AI definitely can, and in some cases, should coexist together.

“I think ultimately anything that we do, any new discovery we make, it’s going to have a positive or a negative effect based on the hands that are using it,” Turner said. “It’s important that we make sure that the tools that we’re using in school especially are used positively here, and you’re shown how to use it positively so that we can have that net positive in the end.”

Despite the uncertainty of the role AI will play in the future, its development and progression aren’t likely to end soon, and so students’ and teachers’ attitudes toward it must evolve as well.

“Make it everywhere, as a matter of fact,” Turner said. “Put it up in everyone’s face because soon enough, when you’re out of high school, it will be everywhere, and if you haven’t had a chance to figure out how to use it by then, you’ll be behind.”

billy joel • Sep 15, 2025 at 10:06 am

love it