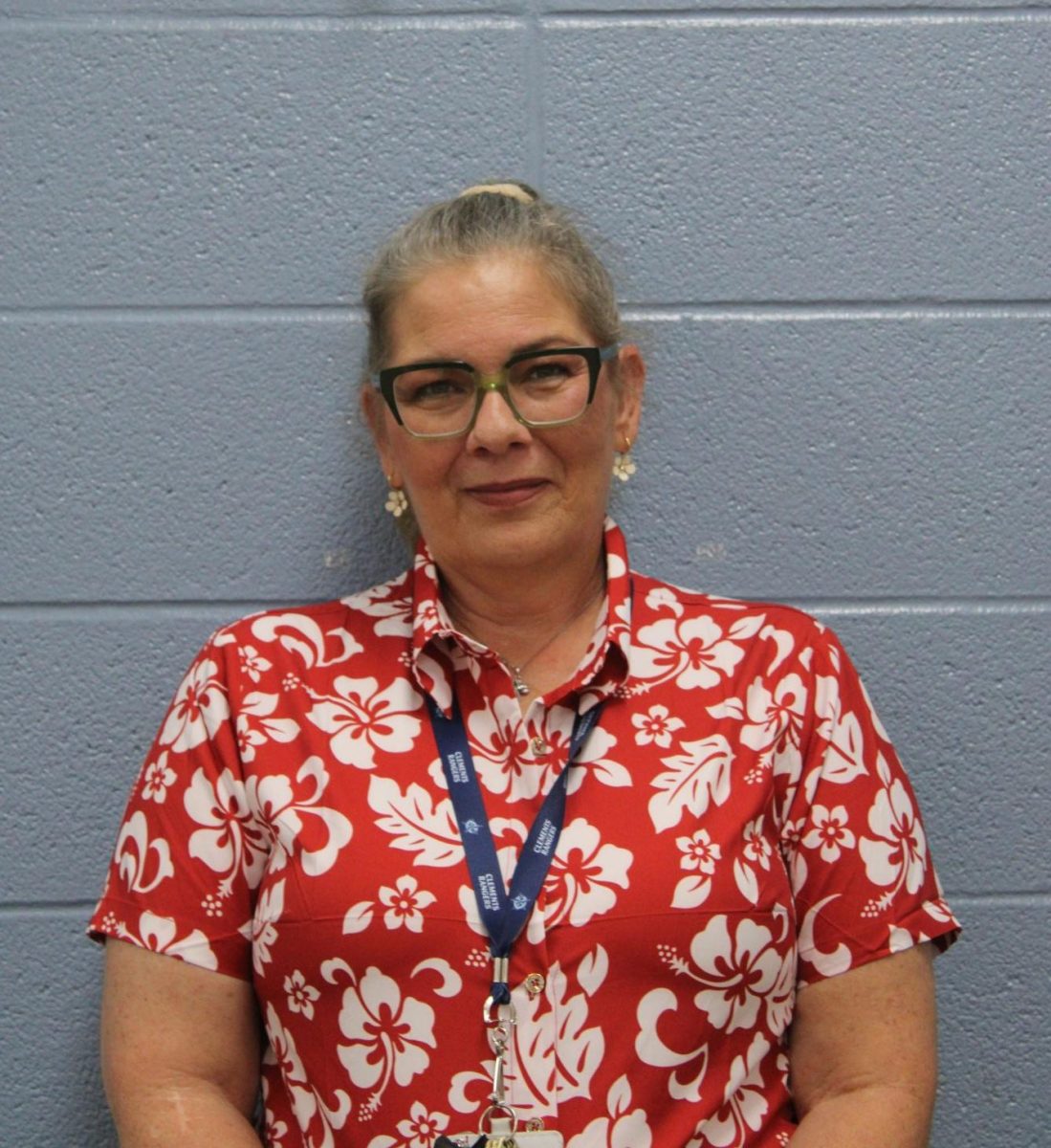

The words are incomprehensible – an endless string of vowels and consonants that are arranged into entirely foreign shapes – like hieroglyphics to the average eye.

A fresh-faced 24-year-old, Chyn Hsu Jing understands none of the presentation. With no recorder, Jing resorts to copying every word down. When she gets home later, she will need to look it all up in the textbook.

“This was the only way,” Jing said. “If there were really problems, classmates would know that you were from a foreign country and didn’t speak the language, so they would be quite patient and tell you what you could do, step by step. But I also had to take tutoring classes to learn English. The English teacher was also very good and would help.”

Initially coming to the United States from Taiwan to get her master’s degree from the University of Texas at Austin, Jing has now lived abroad for fifteen years.

“I still miss [Taiwan] very much, because all my family members are in Taiwan. Only my husband, my two children, and I are here,” Jing said. “It is very emotional, especially during festivals like Chinese New Year when you can get together with family. It’s a nice feeling. Because families in Taiwan are very large, with many people, about 20 or so, sometimes I feel lonely here. But you’ll still be able to befriend different people, so during certain festivals, we’ll get together more often and people feel closer.”

As a child in Taiwan, Jing said her parents gave her a lot of freedom, but studying was “quite stressful” – students had daily exams and tutoring after class every day.

“When I went to college, it was all my own decision, in fact, my parents did not put pressure on me,” Jing said. “I think that it had a deep impact on me because I feel that I will not put too much pressure on my own children. When I teach, you can also sense that I don’t try to put pressure on students unless there is something that I really feel is not right, and I must say something to correct it. Otherwise, basically, I will give children more freedom to express themselves, because I think if everyone’s thinking is closed, they cannot develop.”

Jing earned her first master’s degree in Biological Science Technology from National Chiao Tung University in Taiwan. After moving to the United States and earning her second master’s in Technology Commercialization, Jing said she had to “adjust her mentality”, especially when it came to learning English.

“It’s not just academically that you can’t keep up,” Jing said. “I told my students that when I came here, I actually couldn’t understand anything. Even though I took these English courses in Taiwan, the environment here is actually completely different.”

After completing her degree, Jing worked as an intern for a research company for one year, then worked for the Baylor College of Medicine in the human genome sequencing center.

“Every day is actually a bit high pressure,” Jing said. “We even have to take turns to go to work and get off work. Some colleagues have to come very early. We have to start running this machine and get the results as fast as possible. We are all in a race. So this is actually a step-by-step challenge, right? Step by step, you have to face it.”

Jing began her teaching career in biology, branching off her science background. Only later did she begin teaching Chinese.

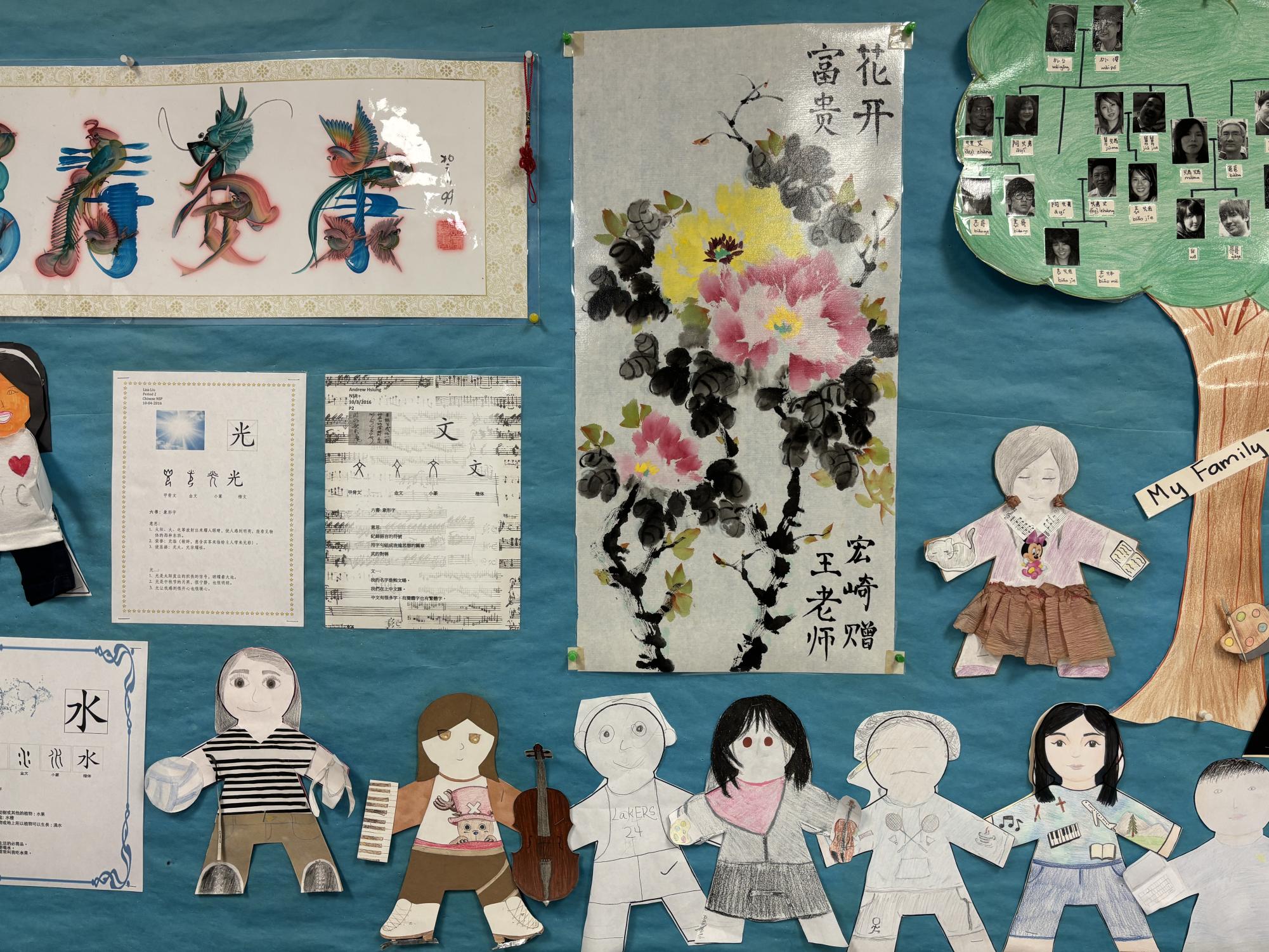

“You use biology every day, right?” Jing said. “What you eat, what protein you eat, all of these are related. So it’s the same with teaching Chinese. If you are in that environment at home, it’s better, because you will definitely encounter and face it.”

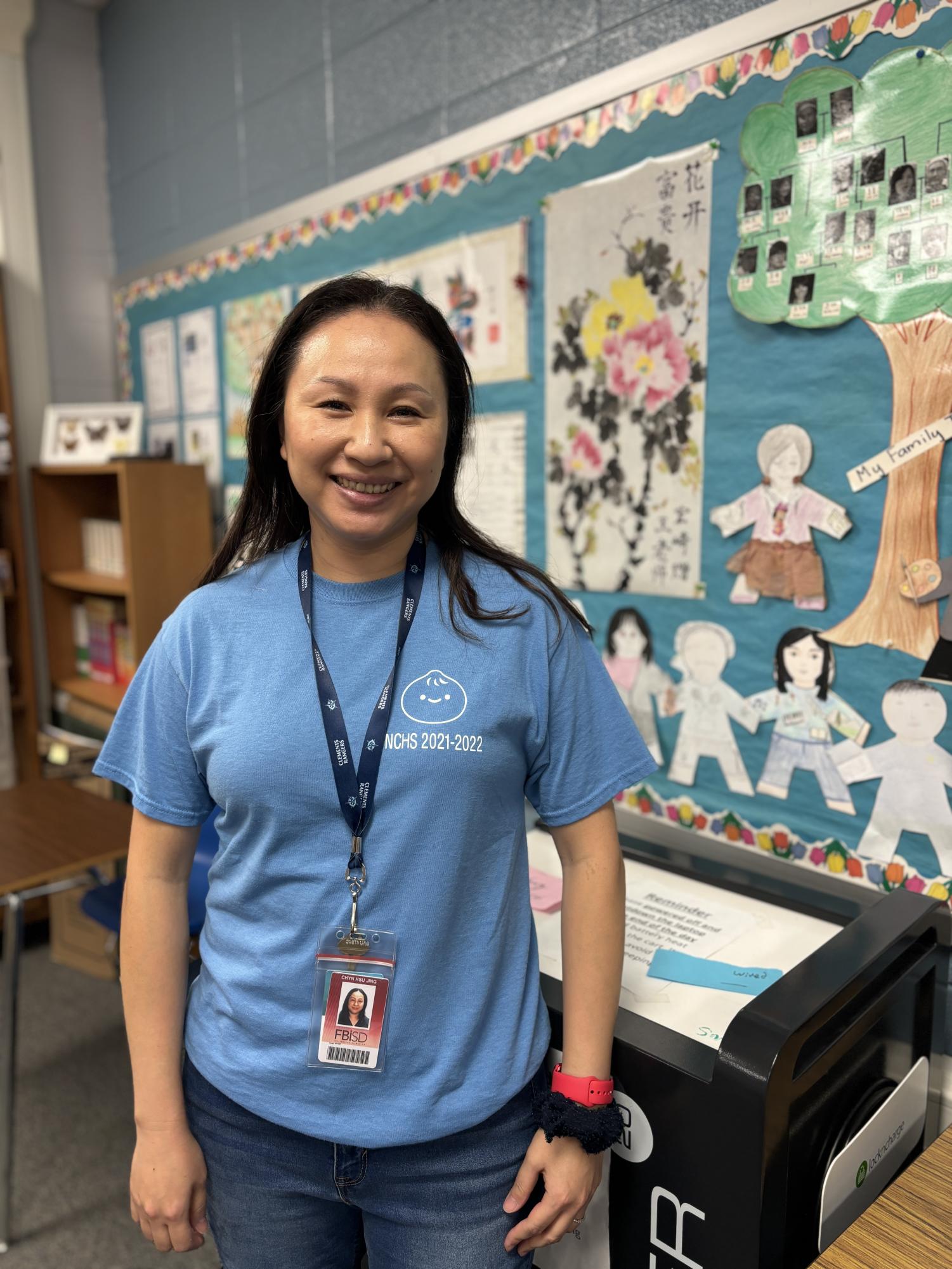

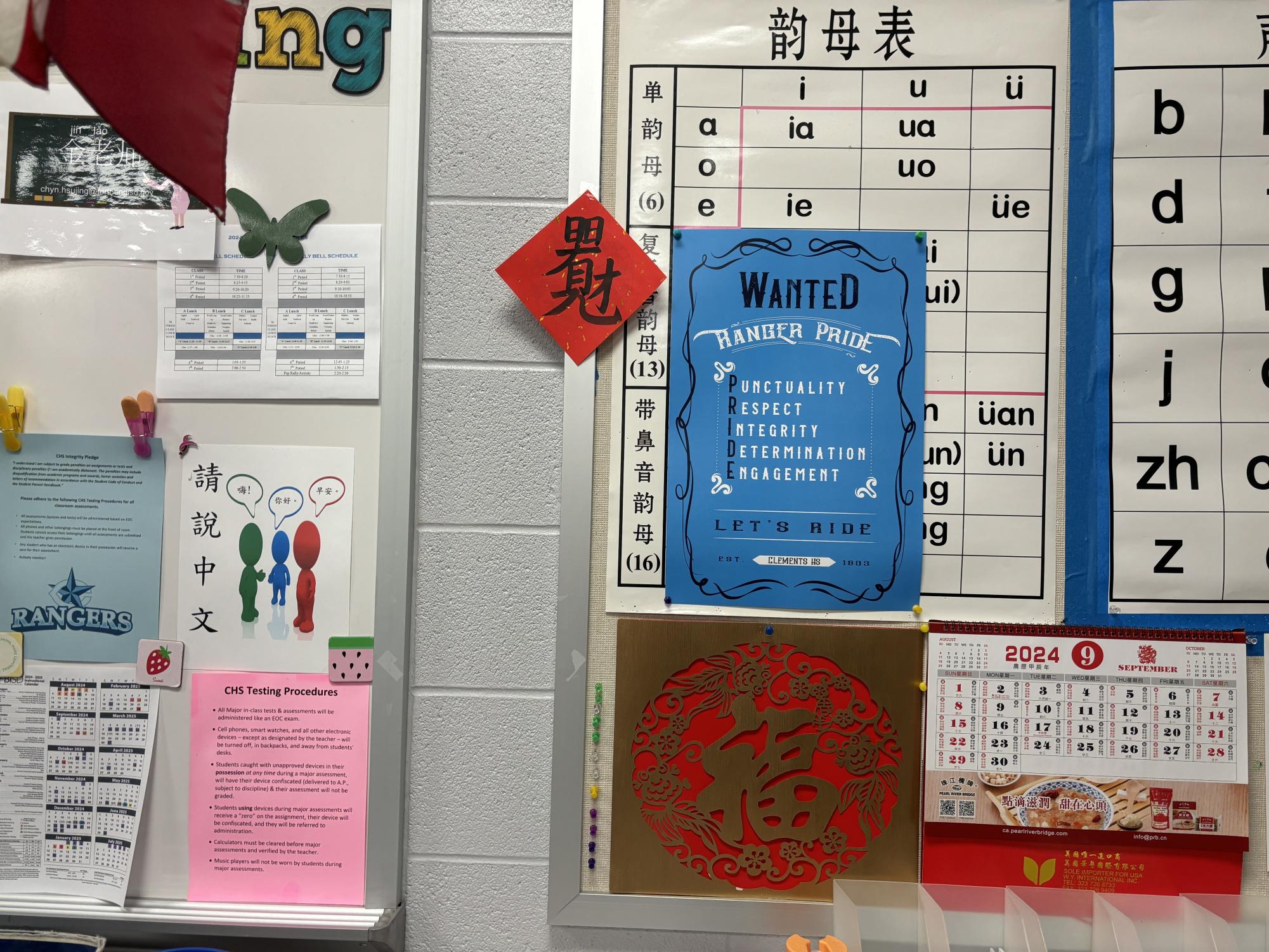

While Jing started out with Biology, she said she has been teaching her Chinese all her life – starting with her own children. At Clements, she teaches advanced Chinese classes, starting with Chinese II and NSP, and sponsors the National Chinese Honor Society.

“I really like that she’s willing to just work together with me,” NCHS President Grace Trinh said. “I don’t know about how Ms. Wang was with the president, but, Ms. Jing emails me, maybe like two or three times a week and we talk things over or I go to her room. I really like that we’re kind of just figuring it out together, and she recognizes that.”

Trinh joined NCHS in her sophomore year to get closer to Chinese culture. While Trinh said she was able to do research through NCHS, the Chinese learning process was not without challenges.

“[Chinese] was my first language, and then I forgot it, so it was kind of a bit of a challenge to learn it back, and it was a little difficult for me,” Trinh said. “In NCHS, it’s pretty apparent that other people’s Chinese or just knowledge is better than mine, but I kind of use that as a way to just learn more.”

The challenges of learning a language can come either from being immersed in a foreign language by traveling abroad, like Jing’s experience, or learning a mother tongue in a different country, which Jing’s students go through. Either way, Jing said she believes the process of teaching Chinese is “very significant.”

“I still miss [my students] now because I feel that these students have made so much progress, but they will not only think of themselves, they will think that ‘I have learned so much’ [and] they will give back their thanks,” Jing said. “I think this makes me feel very gratified. I think some students are thick-skinned, but there are also some who express their gratitude and thank you for your efforts.”

Jing also said her teaching methods have evolved over the years.

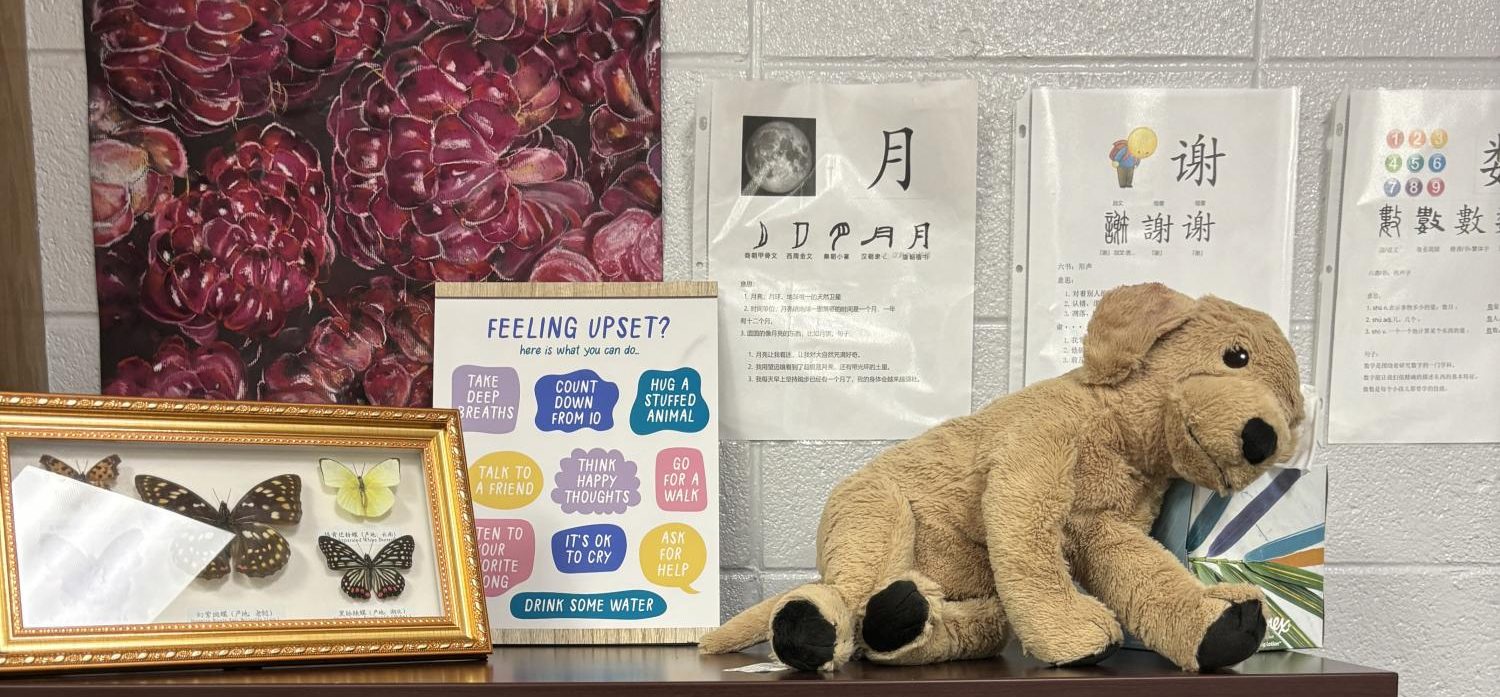

“[In the beginning] I didn’t know how to teach, how to attract students and make them feel that class is fun,” Jing said. “Because I told you that I have been sitting obediently since I was a child. The teacher had power and you couldn’t do your own things. How could I make the students feel that they had to listen, but I wanted to give them a degree of freedom? So I would tell them that if they really have to take an exam, you can, but you have to finish your work.”

Now, while Jing tries to give her students “relative freedom,” one activity she doesn’t tolerate is using cell phones, especially in light of the schoolwide phone ban.

“After finishing their homework, some students would just play with their cell phones,” Jing said. “What should I do? I would go over to the side and see what they were playing with. I would help them play and make sure they die quickly. Then they would quickly put it away. I would use that method to persuade them to put it away.”

Jing said she has to use her perspective as a Chinese teacher to teach her American students. At the end of the day, though, she said she won’t push students as long as they have a general direction in life.

“As a mother, I will tell my children that homework and grades, in fact, I can’t say that I don’t value them, but … you are already adults,” Jing said. “You don’t need me by your side, you don’t need your parents to say anything, so my children are relatively free, but you have to be responsible for your grades and your lessons. You know what you want to achieve, and you have to teach what you should teach.”

Jing said seeing progress is the part of her job that brings her the greatest joy – she herself has come quite the distance from the master’s student who couldn’t comprehend her teacher’s lecture to becoming the teacher.

“I think this is a learning process for me,” Jing said. “I think I am quite happy here so far. Coming here every day is my motivation.”

Note: Ms. Jing’s responses were translated from Chinese to English.