Note: Global warming, climate change, and the climate crisis are used interchangeably in this story to describe the various effects of greenhouse gases on the world that have caused extreme weather, storms and changes in rainfall patterns, ocean acidification, and sea level.

“Helplessness” is the first word that comes to mind when junior Justin Xu thinks about climate change.

For junior Yifan (Jenny) Kuang, “despair” and “hopelessness” are the two terms that surface.

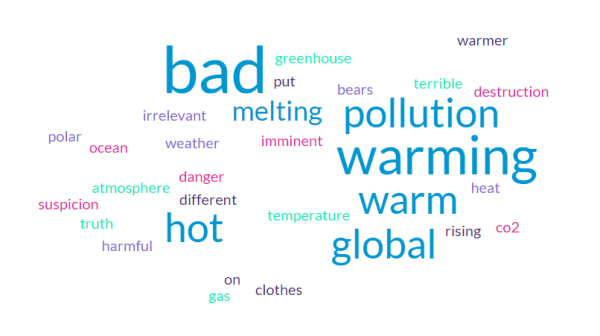

Through dozens of anonymous survey responses collected by the RoundUp in response to the question “What is the first word that comes to mind when you think of climate change?”, “bad” features most prominently, along with “harmful”, “danger”, and “terrible.”

Contrary to the popular narrative is the power of hope as both a catalyst for grassroots change and a vital asset for youth heading into an uncertain environment in the face of the global climate crisis. However, students must also grapple with their limited power and voice as they endeavor to create a future worth hoping for.

“For me, what I experience is that people know about climate change, but they’re not helping,” Kuang said. “They’re just too lazy or they just don’t want to get out of their comfort zone.”

Xu similarly expresses frustration with a lack of action on the part of those in power as well as concern about the gap between the magnitude of the problem and the response so far.

“[I am] not very hopeful, just because the people who have the power to do something and have money just to enact change, many of them aren’t willing to for many different reasons, for example, political or economic or social,” Xu said. “Just doing something like that would have many oil companies go against you if you were powerful enough. I feel like that’s not right, that they don’t do anything, [but] in one way or another you could somewhat understand why they would take a more passive stance unless someone steps up first.”

At the individual level, Xu said that there should be a “spectrum” of how much people care for the environment, dependent on their financial resources. The tradeoff between economically sound decisions and climate-friendly choices – which tend to be more expensive and less convenient – is something AP Macroeconomics teacher Jessica Kelm highlights as one of the primary barriers to addressing climate change.

“Even though people are aware that climate change is a real thing and we need to make better choices, we’re choosing ourselves over making more sustainable choices,” Kelm said. “We’re trying to make sure that our needs and our wants are covered just on a daily basis, instead of making those sustainable choices, and businesses are doing the same thing.”

At the global level, the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty adopted in 2015, established a goal to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius and below 1.5 degrees Celsius if possible. However, Kelm said that political opposition is another barrier that has hindered its implementation domestically.

“There is a conversation across national governments to hold each other accountable and make the right choices, it just makes it hard in a place like a democracy, where you have a lot of politicians backed up by different businesses,” Kelm said. “Politicians get paid by businesses to not push certain types of sustainable laws, things like that.”

When a tradeoff of some kind is demanded in exchange for any amount of environmental action, Xu remains hesitant to fully commit.

“There’s almost no one that would just give up everything about themselves for a cause,” Xu said. “If something big was to be done, someone would have to break these social norms, and just be like “hey, I’m willing to do this for this cause,” just to start the snowball.”

In 2023, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report determined that predicted global greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 will make it likely that warming will exceed the goal set by the Paris Agreement in the 21st century. Already, global temperatures have risen 1.1 degrees Celsius, causing adverse impacts including rising sea levels, extreme heatwaves, droughts, and tropical cyclones.

“Even just in the last five years, we’ve seen a lot of awful increases in disasters and being impacted, so I think people are starting to see that this is bad, that if we don’t fix it, we are going to have a big issue,” Kelm said. “Unfortunately, it’s going to be one of those things where as we see more natural disasters, people are going to have to wake up and see that there’s no more denying climate change, it is a thing.”

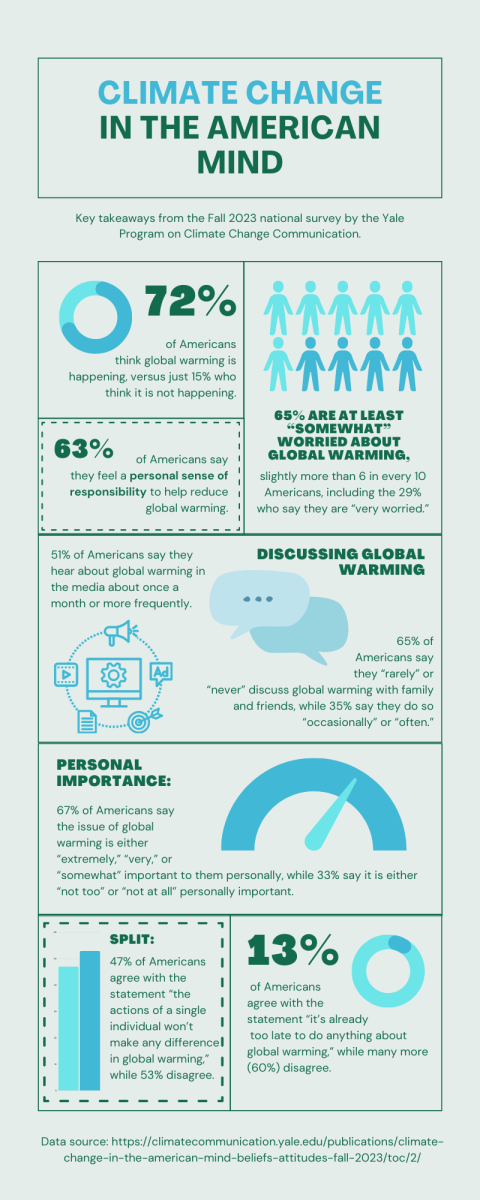

According to a January report released by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 72% of Americans think global warming is happening and 43% say they have personally experienced the effects of global warming. For senior Alex Song, living with Houston’s hot summers and recent freezes pushed the environment into conversations with others. He now serves as the president of the Clements Youth Conservation.

“Activism is meaningful to me because it informs people of problems that must be solved, and motivates the general population,” Song said. “However, I would prefer to tackle problems that I can work on myself, like organizing events.”

Song’s philosophy is reflected in the localized approach that CYC takes, from weekly recycling collections to trash cleanups and tree planting events. However, public opinion remains split on individual action; 47% of Americans agree with the statement “the actions of a single individual won’t make any difference in global warming,” while 53% disagree.

“I could be the most sustainable person on the planet, not using plastic, recycling everything, but that’s one person,” Kelm said. “It has to take a whole group of people, countries, governments, for you to make change.”

CYC Vice President Ali Hussain, a junior, echoes this sentiment as a call for greater participation on a smaller scale.

“Maybe one person won’t make that big of a change, but if you have 50 people in on this, or 100 people, you’re way more likely to do something,” Hussain said. “And one person might not make a change in the rest of the world, but one person can make a change on a local level, on their school, and that’s really important because that’s the thing you’re gonna notice most.”

CYC’s other Vice Presdient, sophomore Tegh Bindra, said that getting people to attend meetings can be challenging, but the passion and positivity present in the club’s mission have served as a motivator for him.

“Even if it seems like it’s very hard to overcome this whole environmental challenge, it’s a good thing to do even if you don’t think we’ll fully completely solve the problem,” Bindra said. “Instead of being down about it, it’s better to take action yourself, instead of being sad and basically saying that “Oh, we can’t do it.”

Even fully aware of the barriers that exist to addressing climate change, Kelm, a nature lover and avid hiker, said she still has hope that the challenge of climate change will be overcome, highlighting the work of companies like 4Ocean, a company that sells bracelets made from recovered ocean plastic.

“Especially for the hope of myself, I would love to be able to have a life whenever I’m in my sixties, seventies, and eighties, of a world that looks like this or taking respect from nature and making sure that we’re keeping up with it and taking care of it,” Kelm said. “Long-term, I have full faith that we’ll be able to maybe not fully adjust and fix the problem, but at least start making improvements in that way.”

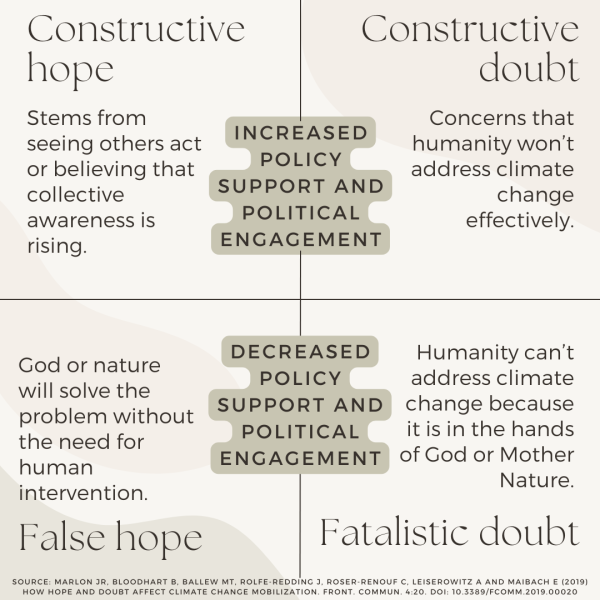

According to a 2019 study, while false hope and fatalistic doubt both place the problem of climate change into the hands of God or nature, constructive hope from seeing others act and constructive doubt due to concerns that humanity won’t address the problem effectively can both motivate political action.

“Hope plays a big part in this,” Xu said. “For example, if I was a normal person and I saw that there was a lot of things being done and significant changes, I would be like “hey, this is a good cause to support.” However, if I see [that] nothing is really being done, and even the things that are don’t have a big impact, I would be like “What’s the point of this?” and steer away from it. So I feel like if there was hope for something, the prospects would be a lot better.”

Although fully aware of the progress that needs to be made, Hussain said he is hopeful for change both nationally, with the United States addressing its responsibility for climate change, and locally, with CYC expanding beyond Clements to Sugar Land as a whole.

“It’s not like you take it as it’s challenging, you take it as a challenge itself,” Hussain said. “This is something that you can change, but you need to put in effort. I would encourage everyone, [if] you think this is really sad or really bad, you should start on a local level.”

For Bindra, the work of organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to fighting poverty, disease, and inequity around the world, serves as an inspiration. In the future, Bindra said he would like to see CYC delve further into air and water pollution, a mission further fortified by those powerful four letters.

“I feel like as technology improves as a whole or any of the environmental measures we’re taking with that, will significantly improve as the years go on, and I feel like companies and big corporations will understand or realize the detrimental effect they have,” Bindra said. “So I do have hope, and I do see us coming out on top of this problem.”