The track’s earthy red dust leaves a residue that lingers.

Illuminated by the relentless sun of countless expectations, the race run by the American high school student stretches seemingly endlessly toward the finish line: college. The runners make their way over hurdle after hurdle – grades, extracurriculars, time management – only to approach one that looms largest of all. Glinting in the daylight, the hurdle that is the SAT has stood unmoving for nearly a century.

They’re nearly there – what is weeks and months of preparation in reality shrinks down to a microcosm on the track. Yet in the eyes of a post-pandemic audience, the footing of that last hurdle no longer seems quite as steady – they hold their breaths, both those that approach it and those that watch on as spectators, in anticipation of its fall.

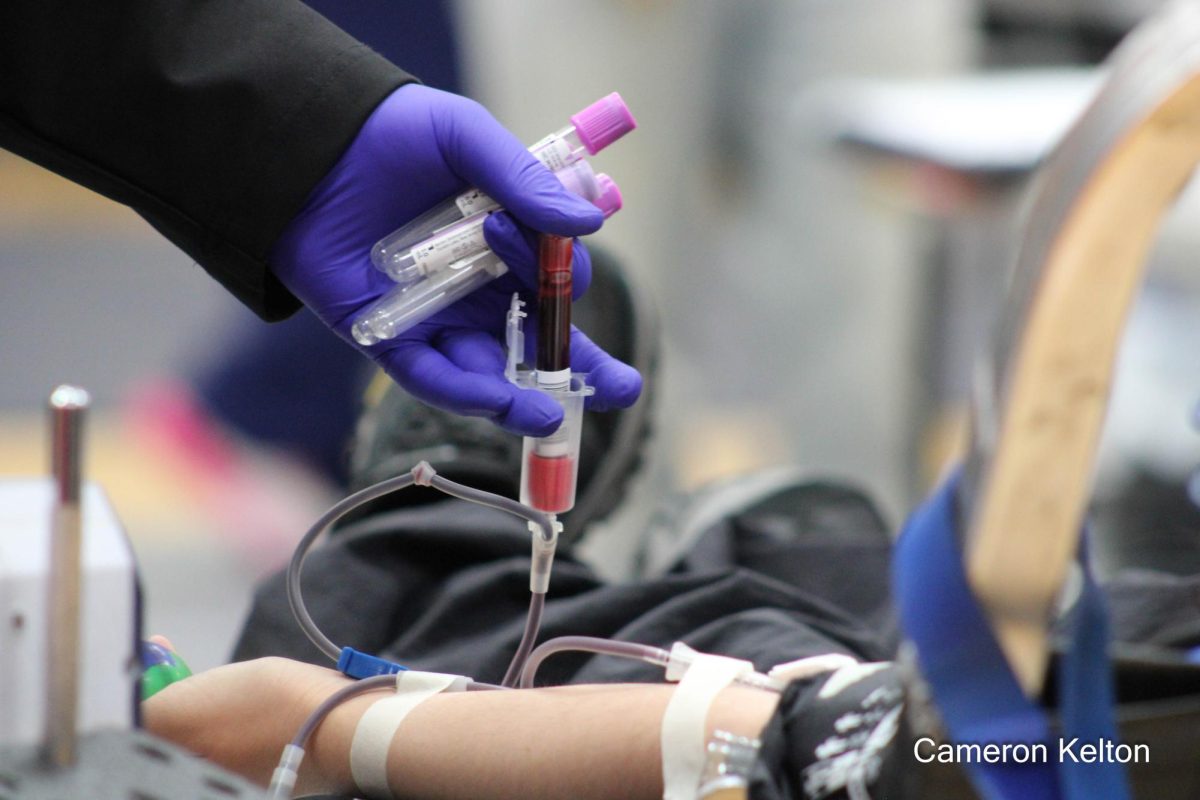

The SAT has been widely used in college admission for almost a century. Though students can register for testing dates during the fall, spring, or summer, all juniors will take the digital SAT on March 6, 2024. Yet, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and findings that have illuminated inequities perpetuated by the test, test scores are increasingly becoming optional.

“Historically, admissions offices, their statement was that [the SAT] is an indicator of a student’s success in college but we know that’s not necessarily true,” college and career readiness counselor Raven Hollins-Crowder said. “As years go by, we are seeing that the importance of a standardized test is decreasing in terms of the importance and the role that it plays.”

Alfred Binet, a French psychologist, invented the first intelligence test in 1905 as a way to determine which students were not learning effectively and needed remedial work. Later, during World War I, Harvard professor Robert Yerkes administered IQ tests to army recruits, generating mass results from which officer candidates were selected. One decade later, Carl Brigham analyzed those results to develop the first SAT, known then as the Scholastic Aptitude Test.

“An aptitude test is more of a future-tense, like will the kid be successful in college or not, that’s kind of what Alfred Binet was talking about,” AP psychology teacher Mason McKie said. “Achievement is more past-tense, so a chapter quiz, a unit test, that’s kind of what have you learned up to that point. Historically speaking, many people have thought the SAT and ACT have been aptitude, predictive nature, but you can definitely make the argument that it’s more of an achievement-based test with all the textbooks and online classes you can take.”

American College Testing (ACT) was formed in 1959, becoming the leading rival to the Educational Testing Service, which had been promoting the adoption of the SAT by universities. In contrast to the SAT’s emphasis on aptitude, the ACT is curriculum-based. Both, however, incorporate the idea of college readiness and they carry equal weight when submitted to universities.

Each year, over a million students take the SAT or ACT – in 2023, the number of students taking the SAT reached almost two million. Yet, the limits of both tests are increasingly becoming clear.

“Sometimes standardized tests don’t actually show the aptitude of the student and their abilities to actually perform in real-life situations,” junior Naayva Agarwal said. “The thing is, aptitude tests only show how much you can do, but then when you’re faced with a situation, you have to think practically.”

Scores on the SAT are determined by the sum of the Evidence-Based Reading and Writing and Math section scores. Similarly, the ACT consists of multiple-choice questions in four areas: English, mathematics, reading, and science. Preparatory courses for both tests can range from hundreds to even thousands of dollars.

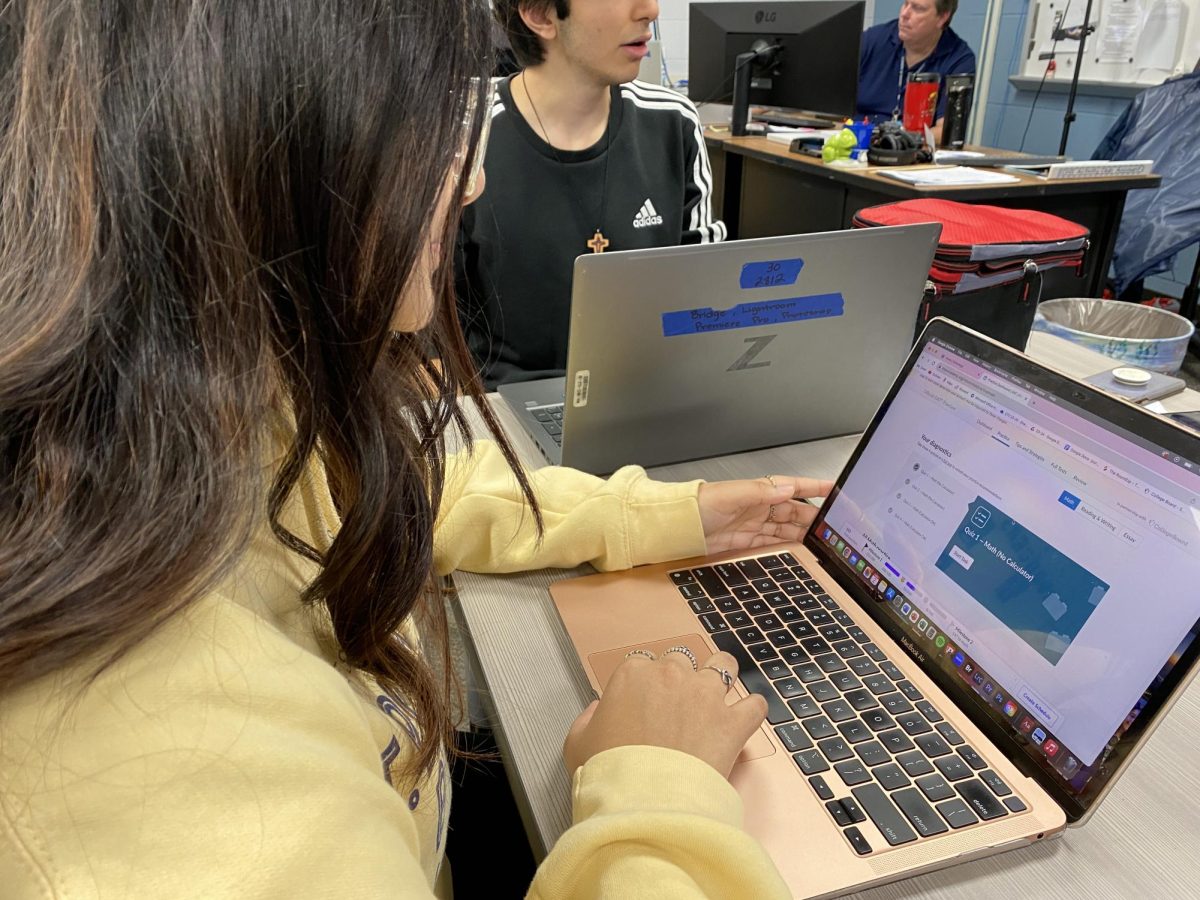

“I did TestMasters for about a month, I took their group class,” Agarwal said. “Currently I am prepping for the SAT by myself, so I do their exam clubs where I go once a week to take a SAT test. I also do Khan Academy practice on a daily basis to kind of just hone in my reading and writing skills.”

Agarwal says she believes SAT scores depend first on time and money, then on a student’s ability or aptitude.

“The more money you can put towards it, the better of a tutoring you get to the SAT,” Agarwal said. “Essentially, this shows social disparities between those that might get lower scores might come from a lower income household compared to those that might get higher scores and come from a higher income household.”

Recent studies on standardized tests, focusing largely on SAT scores, support Agarwal’s thinking. According to one paper, students with a family income of more than $100,000 are more than twice as likely as students with a family income under $50,000 to have SAT scores above 1400 out of 1600 possible points.

Data from College Board’s 2023 SAT report also supports this trend. The mean scores of students from the lowest, second lowest, and middle quintiles of median family income – everything below $86,073 – are all below 1000. Only in the second highest and highest quintiles do mean scores breach 1000. Notably, total mean scores all advance as income quintiles do; from the lowest to highest quintiles, the mean scores are 891, 942, 984, 1039, and 1148.

“Financially, think about why you go to Clements,” McKie said. “You’re zoned here, so can you afford a house to live in a good zone in your area, can you afford Princeton Review, can you afford this extra help, that definitely plays a role. If you can’t, you maybe can be at a disadvantage.”

Clements boasts high average SAT scores in comparison to the Texas average, consistently topping 600 out of 800 for each section, while the Texas average lies around 500. Clements is also located in Sugar Land, where the median household income is $123,733, in the highest quintile. On the other hand, Hightower High School is located in Missouri City, where the median income is $88,426, in the second highest quintile. Hightower’s SAT scores average around 550, near the Texas average but consistently lower than the Clements average.

“At first there was a point to where I thought ‘well maybe it’s a bias, maybe it’s a racial bias, maybe it’s this’ but really it’s green, it’s money,” Hollins-Crowder said. “Those that can afford to have those test prep interventions and companies coming and working with them, it definitely does make a difference. That’s not to say those companies are bad or anything because I know a lot of times they will offer specials to work with students from underserved areas, but I do think it is worth a conversation. You have to consider that there is a gap and that definitely has something to do with it.”

As this disparity has come to light, the connotation that the SAT carries has begun to shift.

“I think that my big motto with the SAT is that one test shouldn’t define your future, and that’s why for me it does carry a very large negative connotation,” junior Juhi Godbole said.

The role that the SAT plays in college admissions has also been called into question. The previously mentioned paper that highlights discrimination in college admissions recommends that colleges stop using SAT and ACT tests entirely, a stance Godbole takes as well.

“I would just get rid of [the SAT] completely,” Godbole said. “I think that what you do over your high school career, whether it be academics, whether it be extracurriculars, I think that should be enough to prove to colleges that ‘hey, I’m a worthy candidate for your school, I’m a well-rounder, I’m a good student overall’. I think that should be enough.”

Increasingly, colleges are adopting that stance, too. Over 2,000 colleges are test-optional or test-free for the fall 2024 admissions cycle. For example, the University of California school system is entirely test-blind, meaning standardized test scores are not considered at all in the application process. More common, however, is the test-optional model adopted by universities like Cornell University and the University of Chicago, in which applicants can decide whether or not to submit their scores. On the other hand, colleges like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Georgetown University still require test scores.

“I don’t think your intelligence can be based on one test,” Godbole said. “I think you should be able to prove it over time. Things like your school grades, that’s something that you can use over time, that you can prove over time. With the SAT, there are so many other factors. You may not be a good test taker, you may not be having a good day on the day of your SAT, and it may not seem like it, but those things do impact your score, they do impact your mentality during your test.”

Especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many students weren’t able to take the SAT or ACT, many colleges are leaning toward the holistic admission framework. For instance, Rice University states that its admission process is an “individualized and holistic … process which examines the entirety of an applicant’s academic prowess, creativity, motivation, artistic talent, leadership potential, and life experiences.”

“I feel like admissions without the SAT are a little bit more fair, but it does increase the amount of effort that you probably have to put into your college app[lication], like your essay has to be better, your grades have to be better, your extracurriculars have to stand out more,” Agarwal said. “All those combined have to shine out more without the SAT, so I still believe that the SAT is a good thing to put as an optional section, not necessarily as a need-to-know.”

College Board identifies multiple factors considered in holistic admissions, including “academic, nonacademic, and contextual” factors. In addition to academic achievement, the caliber of a student’s high school, their personal background, extracurricular activities, and possible extenuating circumstances are among the factors that fall under that umbrella.

“Sometimes students can’t do volunteer work or be part of a club because they have a job, they’re helping support their younger siblings, maybe they’re actually contributing to the household or maybe they’re just at home babysitting,” Hollins-Crowder said. “They’re the ones that pick up their younger siblings from school and they do not have the opportunities to have a job, to be in a club, to participate. I love that colleges and universities understand that first-time-in-college student, there’s no longer just one profile, there’s no longer the 17, 18-year-old coming directly out of high school from a two-parent household who are gonna be able to pay for everything. I love that they recognize that.”

However, standardized tests may still have practical applications outside of solely college admissions. Agarwal said that preparing for the SAT has helped her better her skills, especially in the reading and writing section, where grammar plays an important role. This aspect of the SAT is something that Hollins-Crowder believes can serve a different purpose.

“Reading, writing, literacy is the foundation to our education, and so I would definitely use [the SAT] as an indicator of where the work should be done and ways to do that, but have serious conversations about intervention,” Hollins-Crowder said. “Not just a box being checked or whether they’re prepared or ‘we did this, we did that’, no. What are we going to do? How are we really going to help them?”

As Agarwal and Godbole actively prepare for the SAT, voices for equity and inclusion persist in seeking out a compromise with a century-old tradition, creating a nuanced discourse even without a perfect solution in sight.

“I love that this is a conversation that’s being had and I hope it continues,” Hollins-Crowder said.

Until then, the race carries on.

This story has been revised for clarity.