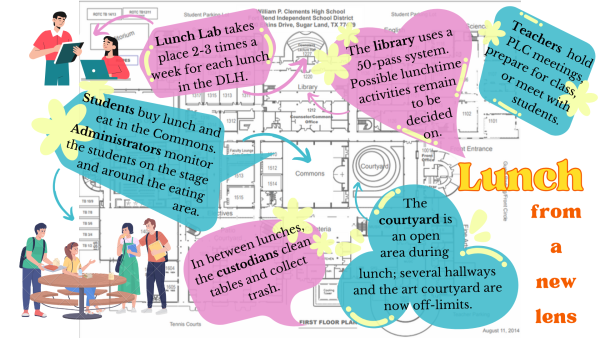

A new lunch schedule of three 30-minute lunches has replaced the previous schedule of two 50-minute lunches. The change has enabled the administration to address disciplinary and safety challenges but has also raised concerns related to scheduling and learning.

Principal Brian Shillingburg said that the new schedule has been a “much better experience”, allowing the administration to tackle the three main issues that motivated the change: custodian workload, student misbehavior, and student safety.

First, whereas under the previous two-lunch schedule the custodial team had to clean up trash left around the entire first floor, students now eat only in the Commons and the courtyard. Though the transition time to clean between lunches is now slightly shorter, custodian Anthony Grant says the new schedule is still overall better.

“Overall, three lunches for me is better, maybe I could say is the best, because remember we were doing one lunch, two lunches, and now with three, it’s kind of more moderate in all different kinds of ways,” Grant said. “It makes the hallways and lockers still cleaner too. It’s still work, but it’s less challenging.”

The limited eating area has also eased safety concerns that arose in the wake of school shootings, such as the Robb Elementary School shooting that took place in Uvalde, Texas in May of last year. Shillingburg, along with other assistant principals (APs), are able to keep track of the locations of all students during lunch now.

Lastly, the new schedule has enabled the administration to address a rise in discipline infractions last spring that seemed to be spurred on by extra time at lunch. Shillingburg says issues like fights can now be addressed quickly by the administrators monitoring the lunch area.

However, Shillingburg acknowledged that implementation of the new schedule has not been without challenges, including lost time for teachers to meet with their colleagues and prepare classes.

“I think it’s probably helpful to the custodians, and that was the goal; I think it’s probably easier for administrators to keep track of where students are, and that was the goal,” AAC English II and AP English III teacher Faith Orsargos said. “I think that the people that were probably hit hardest were the teachers.”

Orsargos says the lost time has made it more difficult to meet with students during lunch and has forced her to not only stay later at school but also complete hours of grading at home.

“I don’t think I could survive if I didn’t,” Orsargos said. “I’m getting the kid to bed and then I’m grading like two hours every night right before going to sleep and that’s just my daily schedule right now.”

Orsargos says that every day feels “fast and furious and nonstop”. Many days, in between Professional Learning Community (PLC) meetings and helping students, Orsargos doesn’t have time to eat lunch.

“I don’t have a common planning period with either of my PLCs,” Orsargos said. “We have to use lunch, or we would have to meet before or after school, and hardly anybody can align with before or after school with all the other commitments. Lunch gets sacrificed.”

Though skipping meals has proven negative health effects like irritability and difficulty concentrating and learning new information, a tradeoff has emerged between eating and productivity during lunch.

“How am I supposed to eat lunch in 30 minutes?” junior Rachel Yang said. “Sometimes the line takes 20 minutes, so I have to bring my lunch into my class and eat during class.”

Though dividing up the student body into three rather than two had made lunch lines shorter and the Commons less crowded, the combined time to buy lunch and use the restroom can take upwards of 15 minutes on worse days (as timed by a RoundUp reporter), half of the allotted time for lunch. As a result, students looking to make up work or attend tutorials often do so at the expense of eating. The reverse is also unfortunately true.

“We’ve seen still an okay stream of kids coming here and there, but there have been noticeable declines in the number of kids coming and the tutors that had previously come,” AP English III teacher and Lunch Lab coordinator Glenys McMennamy said. “I think because they don’t feel like they have as much time to be able to do that and to eat lunch, and so people prioritize just eating lunch.”

Lunch Lab is a lunchtime tutorial program coordinated by McMennamy and AAC Algebra II teacher Michelle Nelson-Archer. Junior Zavier Ahmed says he relied on Lunch Lab “extensively” last year.

“One example of this was when I was absent for Eid, a religious holiday in my religion (Islam),” Ahmed said. “On that day there was a World History AP quiz and a debate assignment due. Utilizing the Lunch Labs that were available to me were crucial factors in allowing me to make up these assignments.”

In past years, when Lunch Lab was available every day for A and B lunch, Ahmed says having Lunch Lab as a backup option gave many students “peace of mind”. This year, although Lunch Lab is still being offered, it is now only available two to three times each week for each lunch.

“For people who need extra support, they may need to find it in some other way other than Lunch Lab,” McMennamy said. “They may have to figure out rides to come to school early and be with your teacher for morning tutorials, or figure out a way to stay after and manage that with clubs or extracurricular responsibilities that they might not have had to otherwise.”

Besides lost productivity, sophomore Dorian Wu added that he “lost friends” after the change to three lunches.

“Several of my friends no longer talk to me because I’m not in the same lunch as them,” Wu said. “Each one is distributed between all the lunches.”

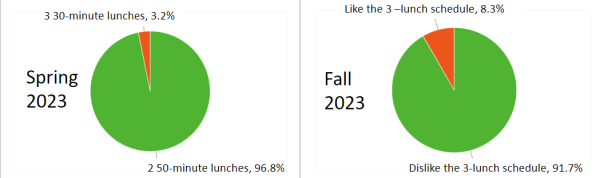

For each of these reasons, the new schedule has been relatively unpopular among the student body. Last year, 96% of students responded to a RoundUp poll in favor of keeping the two-lunch schedule; this year, having felt the effects, 92% of students say they dislike the new schedule.

The poll, however, was conducted only among general education students. Special education department head Melissa Alderfer said that the new schedule had a “spectrum of results” among students with disabilities.

“It was kind of split,” Alderfer said. “Our students with more severe disabilities who really needed that structure really struggled. Some of our students with behavioral difficulties really struggled, [be]cause it’s just have extra time to get in trouble. But then our higher-functioning students really benefited [be]cause they had time to go to tutorials and those sorts of things during lunch.”

The former group, students with more severe disabilities, tend to be students with cognitive disabilities, meaning their thinking processes are impaired. Alderfer says they benefited from 30-minute lunches, as excess free time during the 50-minute lunches tended to cause anxiety and even an escalation in behavioral difficulties.

On the other hand, Alderfer says higher-functioning students, like those with ADHD or learning disabilities like dyslexia, benefited more from the previous 50-minute lunch schedule, as it gave them time to seek help in places like Lunch Lab. Shorter lunches are also more difficult for students with physical disabilities.

“Some of our students just move a little bit more slowly, they might eat more slowly,” Alderfer said. “Some of them are really uncomfortable in the big, Commons-type setting, so they would be able to get their food and go to a quieter, smaller group setting to eat their lunch.”

With a shortened time frame, Alderfer says transitioning to a different part of the building, eating, and then going to class has become a challenge now. An even bigger challenge, however, is staffing.

“General ed students go to lunch, and they don’t necessarily need teacher supervision,” Alderfer said. “Our students need to be supervised while they eat, so that makes it complicated for getting the staff time to have their own lunch and still have students being monitored.”

Teacher shortages exist across the district and state – it’s an issue that Shillingburg highlighted as a precursor and motivator of the change to three lunches. Outside of the special education department, that means teachers like Orsargos are taking on additional classes.

“I now have six classes when I had five last year, so that also was a loss for me,” Orsargos said. “This was like a double whammy year.”

Alderfer says that special education teachers have also taken on extra work, as each teacher also serves as the case manager, or “point of contact”, for some 20 students. Doing so requires annual meetings, interviews, and progress checks, all of which shorter lunches have made more difficult. This loss is echoed even by teachers of general education students like Orsargos and McMennamy.

“We [teachers] had gotten used to the comfort of having more time,” McMennamy said.

McMennamy adds that as a teacher, she would prefer to go back to two lunches. But, she also points out one positive for teachers.

“It used to be for teachers, that lunch was just downtime,” McMennamy said. “I do think there’s a little bit more of lunch for teachers has become lunch again and it can be a time for eating and camaraderie, but it’s probably too short to get a lot of work in.”

Even for an initially resistant student body, three lunches have slowly become the new normal. Student Council President Anna Wang says that although the change has presented many difficulties, there is a silver lining for students.

“I think it’s definitely going to be harder for freshman and sophomores and juniors just because their courses are a lot tougher on them this year and they just don’t get that time that we did last year,” Wang said. “I think this would hurt them a little bit, but this also just teaches them to study at home and get everything done in advance.”

After almost two months, Wang says she thinks that everyone has for the most part gotten used the new schedule.

“I think that the three lunches have obviously been a drastic change for our school but overall, all change takes getting used to,” Wang said. “You just kind of learn to adapt to it.”

Mirroring this sentiment is Librarian Marion Brennan, who opens the library every day, every lunch using a 50-pass, first-come, first-served system. Though Brennan says that lunchtime activities like Lunch and Learn from last year aren’t possible under the new schedule, the library advisory board is still going to try to arrange activities like journaling and pet therapy, a student favorite.

“We’re just going to have to adjust to it,” Brennan said. “I don’t foresee any changes, like going backwards, but I think we’re just going to have to accommodate.”

The challenges presented by the new schedule, even interspersed with unexpected bright spots, are persistent. Yet, Orsargos emphasizes that Clements is a “powerhouse school”, introducing a spirit of resilience to the narrative even amidst overwhelming difficulties.

“I’m going to keep drowning, but I’m going to keep doing well and my students aren’t going to notice it,” Orsargos said. “Teachers are just gonna keep persevering.”

After describing both the issues addressed and created by the new schedule, Shilligburg emphasized one phrase: “Change is inevitable.”

His motto as a new leader in the school rings true even for long-time faculty like McMennamy, whose career at Clements began more than two decades ago – long enough to have seen the change from three lunches to I-lunch to two lunches, and now, three lunches again.

“We had this innovative idea of try[ing] something new,” McMennamy said. “It seemed kind of crazy the first time we did that. The feeling that we’re like ‘oh, this is crazy to go back to three lunches’ – it seemed crazy to go to one lunch or two lunches in the beginning too.”

Having grown up in a military family, Shillingburg says that he was constantly moving around, and eventually learned that something was always “around the corner”. In past years, that ‘something’ was the developmental challenges that the pandemic brought about, in addition to a loss of money and staff. Coupled with a spike in discipline infractions, a mounting workload for custodians, and tragic school shootings in the state and country, momentum for change was at its peak.

“The problems that we were facing were not easy things for just one teacher to do something about, or one person, or one kid, to fix,” McMennamy said. “I think we needed some kind of collective change so we could have a culture shift.”